This essay originally was published on December 29, 2022, with the email subject line "CT No. 148: Autocorrect ground beef."

Since I cut my TV cord in '06, I've been happy to spend my vacations doomscrolling the old-fashioned way: in the bowels of the "guide" section of the smart TV, trying to figure out which of the 500+ channels is worth watching. Wherever I travel, the local communications terroir provides endless vacation joy, a peek into the different shades of American mass communications.

And Southern California, with its century-old comms industry and ostensibly the most kooks per capita of any metro area on earth, consistently provides the best local television tourism. In one short viewing session, you can experience ads for cults and commercials promoting nothing but Jesus; locally produced TV that feels straight out of 1985; and the most bonkers selection of political commercials in America.

That’s why in late August, around 9pm Pacific Time, when everyone had gone to bed at home, I was in scanning the stations hidden deep in the satellite TV guide. Empowered by the endless iterations of cannabis legally available in Pasadena these days, I DMed an old friend, a former Angeleno similarly delighted and disgusted by California culture. We've talked endlessly about Southern California's local TV, so I thought they would be interested to know my latest finding:

"Did you know there is a channel that only shows Wahlburgers?"

Autocorrect ground beef

It's OK if you don't know what Wahlburgers is. According to Google Trends, its cultural awareness falls significantly below other niche burger chains like Shake Shack and In-N-Out. If challenged to name famous American TV/business families, it's unlikely the Wahlbergs would be mentioned along with the Kardashians or the Hiltons.

Depending on the context, Wahlburgers usually refers to either a small chain of hamburger restaurants owned by A-list actor Mark Walhberg's family, or the reality television show about the family's experience running the small chain of hamburger restaurants. A multidisciplinary hodgepodge of cultural engineering, what makes Wahlburgers most notable is its commitment to mid among the spectra of the American family entertainment business: average burgers, generic family business reality TV, and content so mediocre only a satellite TV channel will run it regularly.

While you might rightfully not consider Wahlburgers worth remembering, my phone certainly does. In fact, it knew the word "Wahlburgers" before I could confirm its spelling. By the time I got to the H, my autocorrect filled in the whole word, capital letters and all.

Whoa, I said aloud, channeling Ted Theodore Logan or perhaps Marky Mark playing Dirk Diggler. My phone knew Wahlburgers. How did that happen?

I indulged in the conspiracy theories about phones listening in and privacy, along with my knowledge of how ad targeting, autocorrect, and language models work. It's not like I'd said the word “Wahlburgers” aloud, but my phone seemed to know the mediocre channel had caught my attention.

For the remainder of my California vacation and into the weeks that followed, whenever I typed a word beginning with "w," such as "want" or "what" or "whatever," my phone corrected me. Excuse me, my iPhone insisted across texting and all the apps, I think you mean Wahlburgers. All the W words are Wahlburgers now.

For the next few days I made the LA rounds, from Pasadena to Venice to West Hollywood to Malibu to Goleta to Glendale. In the many hours in the car, I pondered: How exactly did my phone already know Wahlburgers? Did Apple have a deal with AMC television, the network that originally ran the TV show? Does autocorrect come attached to a Complete Dictionary of American Brands? Does this have anything to do with ad tech and digital surveillance?

In my understanding, personalized advertising data is most deeply connected to credit card data, so my phone listening in was unlikely to be part of the equation. Initially, I blamed my phone's insistence on that time I ate at the Mall of America Wahlburgers, perhaps a year or two before the pandemic.

I rationalized it: We ate Wahlburgers because that is the kind of thing you do when shopping with your partner at the MOA and you happen to end up in front of Wahlburgers, and perhaps they had retail tracking beacons or just remembered our $40 lunch purchase via our credit card. Somewhere along the line, someone in digital advertising turned on remarketing audiences, and suddenly my personal data was forever linked with Wahlburgers. I’m well aware that third party ad vendors have trouble forgetting life’s dullest details if they can be considered personalized advertising data.

But I wasn’t being advertised Wahlburgers. It was just autopopulating through my phone's software through no intentional choice. I didn't realize that my passive consumption indicated such commitment—that Wahlburgers was with me, following me for the rest of my life, or at least inserting itself into my texts.

Or, more likely, that Apple changed its autocorrect software to one trained on a larger language model that really loved Wahlburgers, the same autocorrect software that changed "like" to "love" in my texts for weeks before I turned it off.

Whatever the cause, I didn't appreciate autocorrect putting words into my mouth. I didn't want to think about Wahlburgers ever again.

Eventually I explicitly told my phone not to suggest "Wahlburgers," the same way I had to program it to avoid "ducking" all those years ago. In mid-December, I opted out of autocorrect entirely. It still irks me that this change was my responsibility, that if I made no editorial notes in my autocorrect, my personal device would turn my textversations to ground beef.

A far more efficient way of telling a story: Get it right the first time

But I couldn’t make much sense of why the incident bothered me so much until I re-watched Kelly Reichardt's First Cow, a film about the first time people ever queued up for donuts in Portland, Oregon. It's a story about two friends who, tired of being chased and mocked by fur trappers and frontiersmen, start a business in an 1820s Oregon settlement. It’s an American small business story, practical and deeply connected to the humanity of markets. Even if you’re not a cinemaphile or a fan of Reichardt’s other work, I’d recommend First Cow for all the other nerds out there who like movies about business and work.

At the beginning of the film, the audience watches the import of the area's first dairy cow, pulled slowly along the river toward the settlement, a reminder that cows are not native to America. The main characters exploit the cow for profit, attracting fans along with enemies. It's a deceptively understated and nuanced story of a big idea: that nothing in American capitalism happened by chance, that it was all by design.

First Cow is uniquely brilliant in its depiction of the beginnings of West Coast urban entrepreneurship. Adapted from a novel by John Raymond, it's a minimalist western, art about business, grounded in historical research and immense care. Each shot is gorgeously composed, every detail intentionally crafted. In addition to its implicit argument about capitalist enterprise, the film's existence is justification for the persistence of cinema auteurs, the people who can rally the finest collaborators and mold a story into an audiovisual experience via practical effects and old-fashioned storytelling.

When I watch First Cow, the kind of independent film that mass audiences may consider boring, arty or pretentious, I see nothing but craft and intention supporting nuanced ideas about culture, creation and intellectual property. It contains zero personalized relevance to my consumer actions or purchases, and yet I love it for what it is. It's work that I want to embrace and emulate, styles and ideas that I weave into my ethos.

But there's nothing about First Cow that's particularly replicable, which, in the content business, makes it minimally valuable. It is planned, made, edited, and distributed without continuous iterations. There will be no further adventures of the film's main characters, Cookie and King-Lu. Released in March 2020, First Cow didn't even make back its Hollywood-meager $2M budget.

As an established auteur, Kelly Reichardt will continue to make understated, contemplative films about American culture, but as creative industries continue to pursue the iterative business model of tech, the craft-centric style of the individually fine-tuned story will continue to wane.

A framework for content evaluation in the generative AI era

Instead, we get Wahlburgers pushed into our cultural vocabularies, insisting on their presence, whether through 24 hours of average reality TV, or through a computer that can't seem to remember that just because a word starts with a W, that does not mean the user intends to type "Wahlburgers."

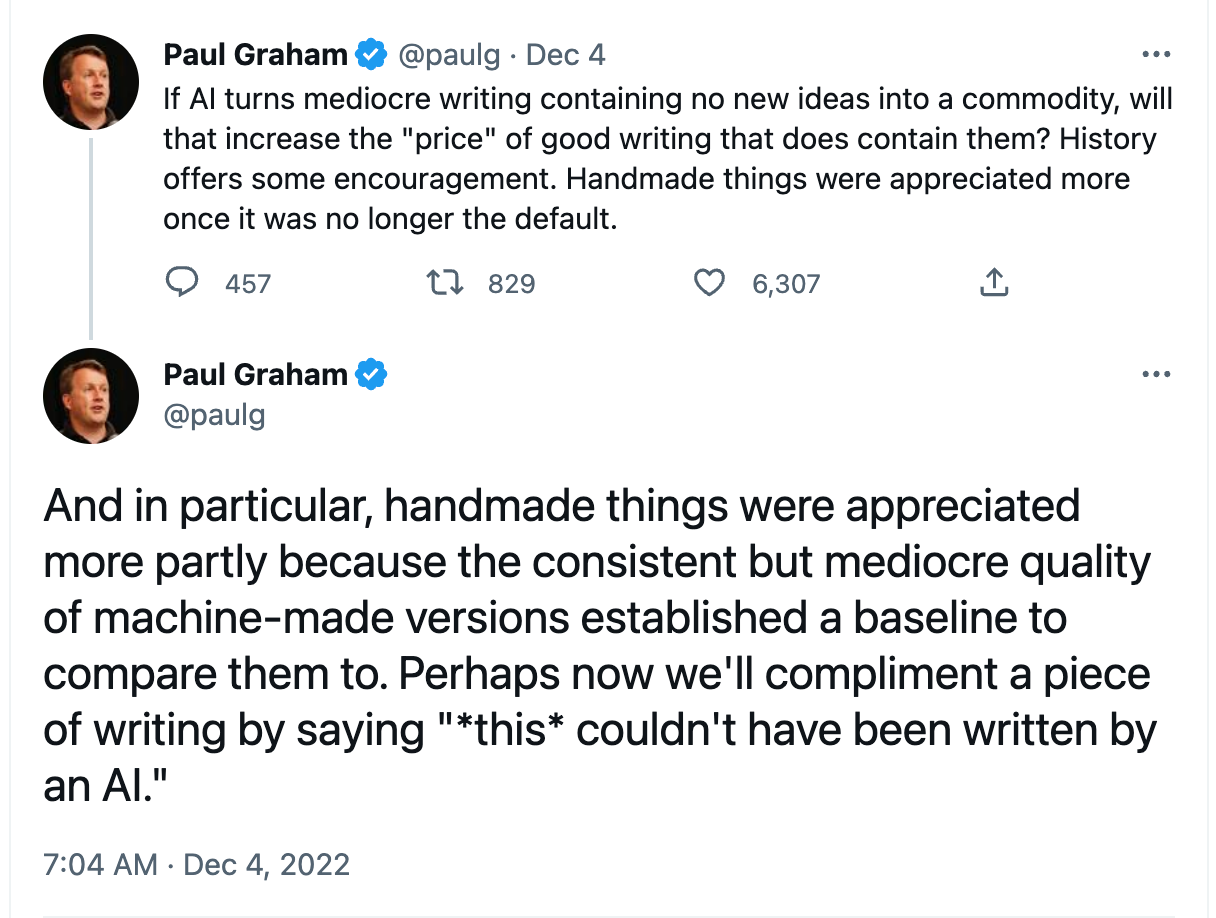

As we exit 2022 and enter into our new world of "generative AI," with all the imperfections of "iterative," large language models and shitty writing, where original content generation looks like bad autocorrects and lazy stereotypes instead of impactful stories, I recommend establishing a new framework for content evaluation: The Wahlburgers–First Cow continuum.

The Wahlburgers side represents late capitalist pastiche, aka another average burger hawked alongside amalgamated family values and small-business posturing. It's a contemporary palimpsest of branding, family and product that ultimately makes various holding companies some sort of profit. Accidents are profitable as long as they can run next to pharmaceutical ads, and mistakes abound in a world so dull it must force itself upon you for attention. It's American mishmash garbage at its finest, mass produced and hoovering up all the attention time the audience will permit.

Meanwhile, First Cow exhibits slow, considered, craft-focused storytelling where no detail is haphazard or accidental. Never before had anyone defined so clearly that cows are an invasive species in America, or that you can still say something profound about capitalism this late in the game.

Content iteration is possible, but it's executed within the confines of the product, not in sequels and next steps and cleaning up messes in post. The themes and environments are meant to be one-off and original, not a minimum viable product but a fully realized work. Some will say it's boring and pretentious, but if you give it your time and attention, it's likely you'll enjoy your two hours and think about it years later. And if we're going into productivity territory, putting aside all artistic merit, First Cow represents a more efficient way of delivering a distinct message to its audience than ten seasons of whatever Wahlburgers was trying to say.

All that said, only Kelly Reichardt, an established auteur who came up in the cinematic glory days of the 1990s, could make First Cow. Newer filmmakers would have a much harder time raising budget, getting buy-in, and finding collaborators who could execute. Its resistance to replication is part of the point.

On the other hand, Wahlburgers represents the umpteenth version of the American dream: the Wahlbergs consider themselves rags-to-riches, and they've built a sustainable business largely on the family personality of affable Boston boys. You can still eat at the Wahlburgers in the Mall of America, in awe of how your big sister's favorite New Kid managed to stick around popular culture for quite so long.

As we move into a new year, one poised to overflow with discussions about "good" and "bad" content generated by computers, I recommend keeping the Wahlburgers-First Cow continuum in mind for your content planning. Although you're making content trade-offs in the name of sustainability, keep in mind that your content doesn't have to be ground beef. Your product can bring in elements of First Cow—intentionality, empathy, craft, stillness and care—while still remaining replicable and sustainable.

After all, Kelly Reichardt is releasing another movie this year, while the TV show Wahlburgers was canceled in 2019. Like many prolific pop culture artifacts of the 2010s cleverly wrapped in branding, it's likely Wahlburgers may have had an outsized influence on machine learning outputs and large language models that Apple used to train its software.

But it doesn't mean that I have to associate it with anything aside from shitty ground beef and an average mall trip. First Cow, on the other hand, will have me considering the origins of America for ages.

Hand-picked related content