This one goes out to Will, without whom I would not know any X-Men facts.

"Lore" is one of my favorite terms to graduate from cheeky internet slang to grown-up conversational staple. Lore is simply legend, often of the unverifiable kind, that accompanies a particular dogma, trait, or decision. The turn of the year is a great time to spin some lore about oneself or one's colleagues, wrapping up accomplishments in a blog post or an all-hands presentation, weaving up a convenient story that becomes codified as the personal and professional state of the year.

Businesses have a rich, lore-filled oral storytelling tradition. "We tried that, and it didn't work, and it's likely to fail forever" exists at every organization that's made it past the ten-year mark. Trend reports are almost universally lore. Strategy meetings and decision-making sessions are filled with the lore codified in annual reports and case studies.

For every clear-cut "we made X change and saw Y result," there are twenty more internal tales that sound something like "We made X and Y change and saw Z and A results, and we think they're connected, so we'll just go with it." The most nuanced communicators are pushed to simplify; communications teams have deadlines to meet; and at a certain point, we have to wrap the tales of the most convoluted circumstances to get home to a hot meal.

In content strategy, internal business lore compounds when you add in the chaos of digital publishing, marketing playbooks, and algorithmic recommender systems. As we make our most heavily researched, deeply strategic decisions what to publish and where, that business lore bubbles up in strange ways. And sometimes, mid-planning, you'll hear something like, "We have to build out an entirely new content campaign that doesn't fit into our existing plan or budget because Wolverine is Canadian and his skeleton is infused with adamantine."

Or maybe a new stakeholder will chime in with something like, "Gambit has a long staff and throws cards, and that's why we need to post three times more often."

Obviously, your stakeholders aren't spouting character descriptors about the long-running Marvel Comics series X-Men. But the explanations they provide are often easily substituted with what I think of as "X-Men facts."

What are X-Men facts?

Probably 40% of my global peer group could confirm that yes, Wolverine is Canadian. The superhero's origin story is fifty years old and has been repeated many times across media. His Wikipedia page is heavily edited and exceptionally well-annotated.

And Wolverine's not alone! There are facts a-plenty when the mutants keep mutating into new spinoffs and remakes. There's a deep library of X-Men facts to choose from, with canonicals and variants. X-Men facts are repeated extensively, not only in Marvel comics and movies, but also reported in Wizard magazine, nestled in the scripts of indie film classics, as answers for trivia nights, memed into oblivion. If you get X-Men facts wrong in mixed company, a correction may be issued. Wolverine is from Alberta, not Saskatchewan.

But despite the proliferation of information about Wolverine, he does not exist. The X-Men are works of fiction, stories developed by a cadre of men working in an office, trying to bring home a hot meal. And we all know that when we repeat X-Men facts as if they are sports statistics. But they are not sports statistics because the sports feats were accomplished by people, who pay taxes and whose skeletons are made of bone.

In the field of self-help, "X-Men facts" are sometimes called "limiting beliefs." I'm sure information science, philosophy, logic, and rhetoric all have their own nomenclature for the idea. But I'm taking the anti-intellectual, poptimist route: The best term for a phenomenon is the one the intended audience is most likely to understand, and I'm betting this crowd knows some X-Men facts.

"The Algorithm" as a lore signifier

When people talk and write about "the algorithm," our great synecdoche, I mostly hear X-Men facts. There is no single algorithm, no clearly defined set of rules across platforms, but everyone understands the common observable experience of the internet. "I was talking about Costa Rica the other day, and that night the algorithm showed me an ad for Costa Rica!" is reliant on the implied X-Men fact that the phones are listening to all of our conversations, always.

The technical explanation is that the ad networks run by Meta and Google can piece together enough information from your credit cards, location, and networked browsing data that they don't really need to listen in on your conversations to serve the ad. Also, it's Minnesota in January: who isn't thinking about a Costa Rican vacation? But I'm not going to say that because you're right, the effect is the same: the ads seem to know way too much about you, and the algorithm gives you the ick. I agree! Mystique's a shapeshifter.

X-Men facts run rampant in digital marketing, where teams believe half-truths about content success that have never been based on anything but a few blog posts from a handful of entrepreneurs, patent-scouring practitioners. "SEO algorithms prioritize longer content, so we can only publish blog posts that are 1,500 words or more," is an X-Men fact, and it's difficult to challenge.

Natural language processing algorithms and curious human readers alike enjoy longer content because it helps us make better decisions and understand the complexity of a topic. Longer content signals expertise. In-depth, well-researched pieces tend to do well in organic search when well-optimized. And 1,500 is not that many words, when we are talking about how many words should be in a feature article. I am not going to dispute that.

But yeah, the forces we think of as SEO algorithms don't work at all in the manner described in the sentence above, and ideally we'll talk about appropriate content length and medium after we get the strategy down (also, don't even get me started on blog posts)! Probably 90% of what I read online about SEO and digital marketing best practices are X-Men facts — situated in a fictional environment, but true in some scenarios, under some conditions.

Why do algorithms process and remember X-Men facts better than more traditionally studied subjects?

Natural language processing is the part of "the algorithm" that reads content. NLP technologies scan available content and determine important words and phrases across the body of work, then classify them, but all with some relational math involved. Eventually, after much repetition, the machine learns that yes, Beast mutated because he was exposed to nuclear radiation as a child.

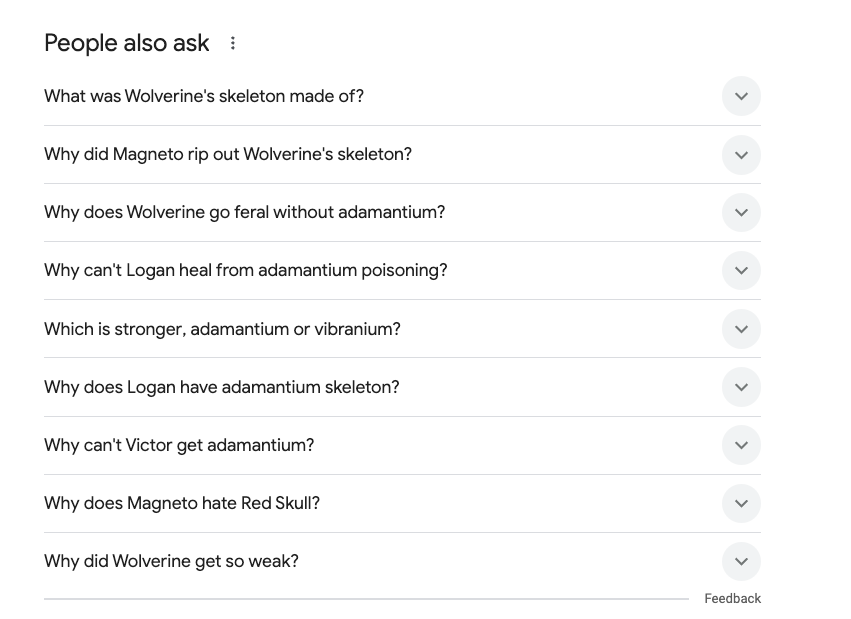

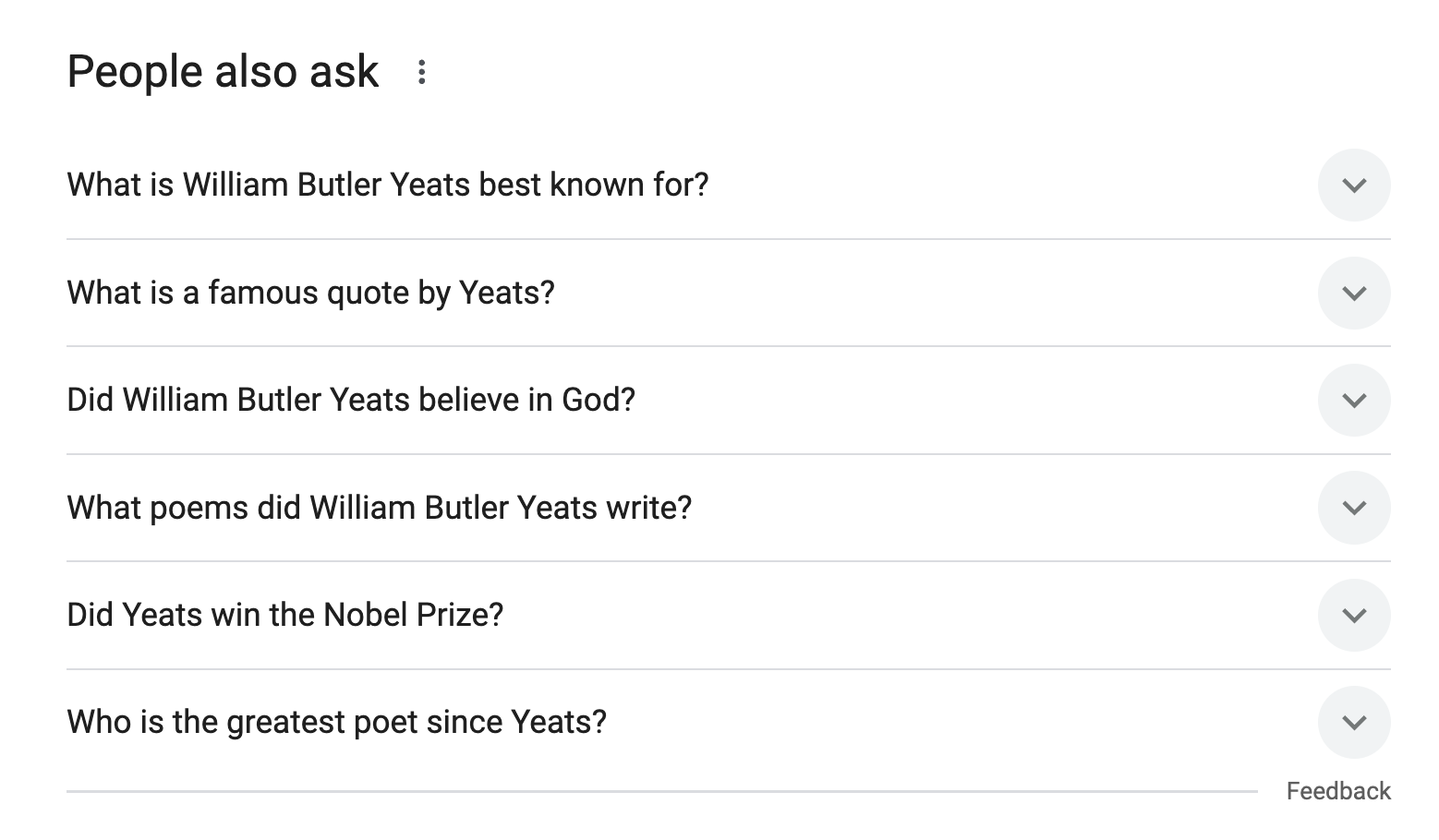

Search engines and language models have long been built on X-Men facts—the consistently published tentpoles of a shared culture with a tenuous connection to reality. Whether in conspiracy theories or free marketing trends research, socially engineered influencer brawls, or affiliate-backed product reviews, X-Men facts proliferate training data. It is far easier for Google to ask a fair series of follow-up questions about Wolverine than it is, say, about legendary Irish poet William Butler Yeats.

All I wanted was one detailed follow-up about the widening gyre.

When I scan the socials and see a few good thoughts, but mostly half-baked semi-facts about content strategy and search optimization and funnels and who is taking whose jobs, I remember that this whole digital knowledge apparatus, while it feels very established, is still on quite shaky ground. I look at the collective of how it's going so far, and it feels like an adamantium skeleton: very cool-sounding, an easy subject for lore, looks great in illustrations, but most definitely a fictional construct.

Hand-picked related content