This essay originally was published on June 9, 2022, with the email subject line CT No. 126: "Attention, Hacks."

This post contains a mild spoiler for HBOMax's Barry, episode 5: "crazytimesh*tshow." Unless you're a rabid Barry fan who hasn't watched the episode 3 weeks after it aired, you shouldn't be too shocked. Also, I haven't watched past episode 5, so maybe my point gets even developed further across the rest of the seasons, but considering it's the C plot in a single episode, I doubt it goes anywhere else.

In the early 2000s I avoided watching ER with my medical student sister. She would comment every time the story was medically or professionally inaccurate, and I rolled my eyes. As with most fiction, the professional details didn't matter as long as the story was good and the universe remained consistent.

These days I find myself making the same kinds of nitpicky comments when I watch tv shows whose plots hinge on algorithmic decision-making. In contemporary storytelling, algorithms are a convenient deus ex machina, an inscrutable event that changes the story in the blink of an eye. In television and movie narratives, feeds represent an environment beyond a character's control, the codification of systemic failure. Algorithms take on the role bureaucracy and elite gatekeepers played in 20th century novels and dramas. In fiction, algorithms are near universally flippant, negative, the uncaring and punishing god of pure capitalism.

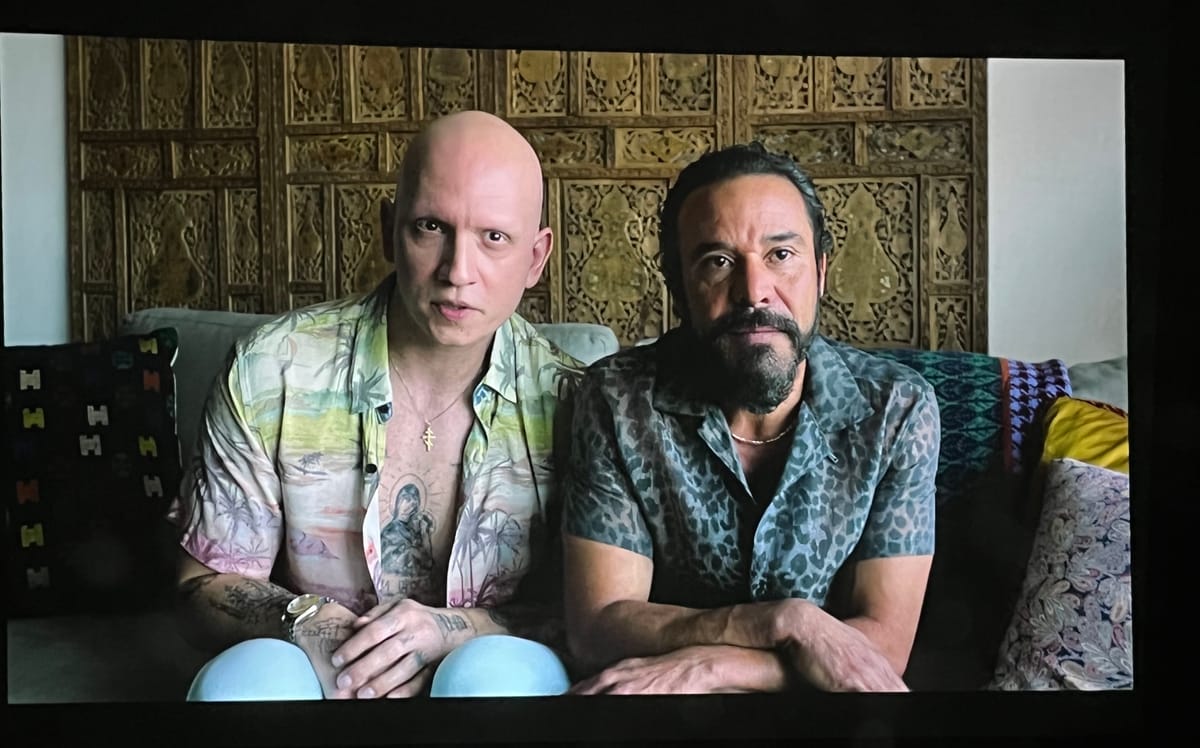

Barry is very peak TV, a half-hour dark comedy that's 90% about a professional killer coping with his murderous nature, standard antihero stuff. But Barry has a girlfriend, and that girlfriend dallies with an algorithm, and suddenly it's relevant to this newsletter.

In season 3, episode 5, the character Sally, self-serious and comically obtuse, has pored her heart and soul into creating her own TV series. She is the writer, director and lead actress; her face is literally the advertising thumbnail for the show. At the show's premiere, she learns that her work has received a 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and she's ecstatic.

The following morning, she gazes at her own face as the streaming service's hero image when her show suddenly disappears. Her work is nowhere to be found on the service. At a meeting with a streaming executive, Sally is informed that her show has been cancelled, less than twelve hours after it premiered.

"The algorithm felt it wasn't hitting the right taste clusters," the network exec says.

Sally, stymied, argues that her Rotten Tomatoes metric proves it's worth everyone's time, that it barely had a chance to reach its core audience. After all, the network invested time and money into Sally's project. But in this case, the critical aggregator metric (Rotten Tomatoes) doesn't stand a chance against the predicted return on investment (the streaming network's proprietary black box of data).

The audience identifies with Sally's indignation at the algorithm's swift dismissal of her art. It's a familiar feeling for writers and creators, the algorithm that deems content unworthy of pursuing. I love the executive's language in her dismissal: "The algorithm felt," reflecting both how executives occasionally speak and the godlike deterministic power businesses can give to algorithms.

But Sally's attachment to her own KPI, also a black box of dubious merit, is equally unfortunate. I know Rotten Tomatoes holds some clout in the entertainment industry for measuring critical praise, but it's every bit as problematic and arbitrary as every other ranking algorithm. It's just a single point in the plot, and it's never the whole story.

The writing team on Barry most likely doesn't really understand algorithmic decision-making or the value of good stories, and they don't have to. But they're counting on the fact that the audience perceives algorithms as arbitrary and ruthlessly deterministic. In legacy creative industries, algorithms are the anti-art, the angry god, the unflinching paper-pusher.

But the artists are aping algorithmic styles and decision-making. Algorithms and their misinterpretation are informing and creating new art, like it or not.

Immediately after Barry, I watched the pilot of Pistol, Craig Pearce and Danny Boyle's Sex Pistols bio series. I cut my teeth on Trainspotting and Velvet Goldmine, so it's hard for me to look away from attractively cheeky punks gallivanting in dark clubs with their guitars. After I got past my initial delight—Pistol is designed exactly for my personal taste clusters—I realized that I absolutely hated the editing.

Pistol is edited as a constant montage: the camera rarely lingers for more than a few seconds, and what feels like every scene is a mix of the actual characters, flashbacks from the characters' memories, and archival footage of 1970s Britain. It's like someone created a nonstop TikTok, an intentional chaos feed that never stops to consider its long-term goals. You could argue that's a rock n roll vibe, but the editing is so slick that pure punk fuckoffery feels miles away.*

Like a contemporary feed, the constant attention hacking eliminates all subtlety, and every plot point or character development is repeated in dialog, then depicted, then repeated again. It's as if the Sex Pistols never ended and just just kept putting out copies upon copies of that one record they released, a new mimicry every year from '77 to '22.

The entertainment industry is creating television that looks like feeds, and that gives me pause. It feels like a misinterpretation of a single data point, a bad ploy for attention-attraction. I hope the experiment is short-lived, for my brain's sake.

Hand-picked related content