Twenty years ago I had my first job in content management. At the time I thought I was ad-libbing to fill in the blanks, but in hindsight I see the foundations for a weird, winding and fruitful career.

Unlike many of my peers, I couldn’t afford to take one of the unpaid internships that New York companies prolifically offered in exchange “for experience.” I had to make money if I wanted to afford all the concert tickets, records, booze, and bodega bagels I desired.

After a short search through my university’s job board, I landed an interview at a historical image licensing agency whose clients were textbook publishers, periodicals, film production companies and other researchers. They competed with the likes of Getty and Corbis but fit their extensive collection of slides and prints in a modest Park Avenue office suite.

When editors or producers needed pictures—reprints of old Thomas Nast cartoons, 1930s film stills, classic works of art, Colonial-era newspaper woodcuts, and the like—a tiny crew of researchers processed their requests, plucking the requested selection of slides and high-resolution prints from one of the three main filing areas. The images were packaged and sent across the city via mail or messenger, where they were scanned or reproduced, with the hard copies to be returned at some later date. My job was to refile the physical copies of each picture once they made their way back to the office.

“Someone recently filed ‘Molly Maguires’ under Historical figures – Ma and not under 19th century political movements – Mo,” the septuagenarian founder clucked during my interview. “In this case Maguires is not a last name!” I assured him that I wouldn’t make such errors, that I’d read A People’s History of the United States and would consult the company’s library of history books if I found an image and wasn’t certain where it belonged.

“Good,” he said. “Now, can you tell me, who is Elizabeth Bennet?” I delivered the response to his satisfaction, not because I was a literature student, but because my mother frequently watched VHS tapes of BBC’s Pride and Prejudice while she did housework. It didn’t matter where the knowledge came from, just that I had the answer at the ready. The founder seemed pleased that he could still find young people he could trust with his archive, his business, his life’s work. I was offered the job, a rare part-time role in the heyday of unpaid publishing internships.

The gig was ideal for a college student, not only because I had a knack for American historical and cultural trivia, but also because filing images was easy when hungover. I could return the immense backlog of previously used pictures at my own pace, alone at the cabinets with no one watching my work, as long as the researchers weren’t finding mistakes in the cabinets.

“Leading” the digital transformation

After about a year of organizing purely physical images, my duties changed. I’d worked my way through the backlogs and filed so many pictures that my role had become redundant. Lucky for me, my employer began what corporate consultants now call Digital Transformation. As the youngest, most expendable staff, I was the obvious choice to do the grunt work of the great digitization experiment: to scan and enter the pictures into the company’s brand new database.

The hours I’d previously spent filing were now devoted to scanning and data entry, which I could also do hungover. I scanned each image and typed its caption manually into the database. Alone in a back office, I soundtracked my scanning with the cds I brought. On the days I forgot my own music, I typed along with Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, since The Flaming Lips made their entire new album available to stream free online.* A typical shift comprised four back-to-back playthroughs of Yoshimi and seven or eight scans— about one scan and database entry per half-hour, depending on how well I’d bounced back from the previous night.

*Probably destroyed my colleagues’ internet speeds when I was streaming it, too, but no one seemed to mind. Oh, the days before the celestial jukebox!

My first encounter with keywords

Half a career later, I can look back and clearly see in my first job the mingling of physical and digital, of old publishing and new formats colliding. But at the time it didn’t feel like a brave new world of digital media or the forefront of digital content management. It was my day job, no glamour or glory; fulfilling paycheck-wise but mostly tedious. It was just scanning historical pictures and typing their captions.

Oh, and filling in the keywords field.

My employer licensed a specialized image database software, designed to manage print-quality images. My job was to fill it with data. I was in charge of a basic form with several fields, two of which I was required to fill after scanning in each picture: The caption, which had been written on a typewriter and physically attached to each file some time ago, and keywords, for which we had no precedent.

The employees in charge of the digital transformation were so excited they got our aging owners on board for a digital database, they didn’t consider the use cases of the database and how it should be prepared. They’d have a database! A searchable database of their own archives! Finally! But like most legacy businesses oversold on software, no one understood how much human input or maintenance the program would require to function in the future. I’m sure the sales pitch from the software manufacturers went something like, You just scan your collection, and boom! It’s searchable! Digitization! Transformation!

But, of course, a database like ours was not searchable on its own. Automated text recognition like OCR barely existed in private companies in 2003, let alone image recognition of historical political cartoons and film stills. The only thing that made the image searchable was the metadata text in the database, aka the keywords I was entering.

The ability to use their new digital investment, the one that would power their business into the next twenty years, was in the hands of a part-timer—a 20-year-old college student with no real goals beyond Go Dancing at Cool Parties. I was a liberal arts undergrad, and aside from my early love of presentation software, I had zero knowledge of computer science or database taxonomy best practices. Until I started working at the image agency, I didn’t know that archival systems existed outside of public libraries. But here I was, on the cusp of a new era, entering keywords for the very first time.

Because I already knew the company’s filing system inside and out, my keywording approach replicated the labels I found in the cabinets and the words in the caption. For example, an image of the Molly Maguires would receive the keywords: 19th century political movements, Irish American, 1877, Pennsylvania, execution, secret societies, because those were the most prominent in the description, or the name of the category. Without consulting my colleagues, I constructed some sort of ad-hoc system: include the name, place, date, decade, its archival filing category, and the most important words in the caption. Whatever I devised was primarily for my sanity, so I could fill in the blank field and move on to the next image.

Why you shouldn’t let the greenest hire determine the company taxonomy

The many deficiencies of my system were brought to light when the company brought in a second part-timer to accelerate the transformation: my roommate, G. (Family-owned companies love hiring people they already know.) Her job was the same as mine, except she didn’t have the institutional knowledge of the archive’s filing system. Since only one of us could use the scanner at a time, we worked different shifts, and although we lived together, G. and I never discussed our workplace. As a result, we never shared with each other how we were keywording the images we entered.

Several months into the digitization project, one of the researchers wandered into the back office. He’d been working at the agency for decades and like everyone else there, knew the collection inside and out. He’d been reviewing some of the entries in the new database and was curious about the contents.

“So, can you tell me, how are you adding keywords for each picture?” I explained my system, and he nodded in assent. He wondered whether we should be adding the keywords “man” or “woman” on every file that depicted a man or a woman, regardless of historical context. He explained that clients asked for images that way, that sometimes they were just looking to print a few generic people from a particular era. “And also,” he asked, “Is G. keywording the images in the same way?”

I don’t recall how I responded, but I remember thinking, But that’s so much work, and we’ve already scanned hundreds of images. You already know what’s here anyway. And I can’t put in every single possible keyword that someone might search for. How could I possibly know what people wanted to find?

It was an immature rejection of valid questions: Who was going to be using this database of pictures, and how? Whose job was it to make it useful? Could the way we’re labeling data be different from the way someone might want to find it?

After two years at the historical image company I moved on to lower-paying but sexier book-publishing internships. After college I said goodbye to all that, moved away from New York and book publishing, went to graduate school, managed some websites, and bounced about unrelated communications jobs. That curious little image agency fell off my resume, and the process of keywording became mashed up with other memories, just something I did for money once back in the day.

It wasn’t until my first SEO job that I tapped back into the experience of the digitization project, the keywords, and the researcher’s line of questioning. I had been asked to make a keyword map, a common website optimization task where a unique keyword is assigned to a webpage. Our team would supply optimizations for each page so it would rank in Google search.

How and why are keyword maps important?

Websites are seemingly endless, which many businesses interpret as an excuse to make a new page of content every time they want to discuss or announce anything new. New pages about similar topics are added, but never culled or organized, and websites grow out of control. Neither human audiences nor search engines are adept at processing or managing several pages of redundant content on one keyword.

Get schooled in audience research skills from the author of this article.

When you've been dealing with keywords since 2003, you pick up a thing or two. Learn how to choose and use keywords from a seasoned professional.

Take the courseBecause Google needs to provide a variety of search results for general interest queries, it typically doesn’t surface more than one URL per domain for a user query. If you have two pages that have keywords that are too similar on your website, Google’s algorithm won’t be able to choose between them, and both pages will rank lower in search results when a user submits that prompt.

The SEO world likes to call this cannibalization, but I’ve always called it split organic search equity: When you have similar content spread across too many webpages, the search engine won’t know which to choose when prompted, and so Google-as-Solomon cuts that metaphorical baby in half and doesn’t rank any pages highly.

To tame a wild website and consolidate content equity, that one page ranks appears more often in search, SEO strategists choose one website page to be the primary source of information about a specific keyword. We review the site and choose the most appropriate website page for each topic, using that keyword to guide the assignment. If a website doesn’t have enough content to support a target keyword, we advise the client to create a new page addressing that topic.

Keyword maps: The tool to bridge your content with the audience’s expectations

While making my first keyword maps, I experienced a revelation on the level of “Do You Realize??”: I was back in the Park Avenue office, staring at the blank database interface, and it was my job to fill in the keywords.

Only this time, I had a guide: a keyword research document.

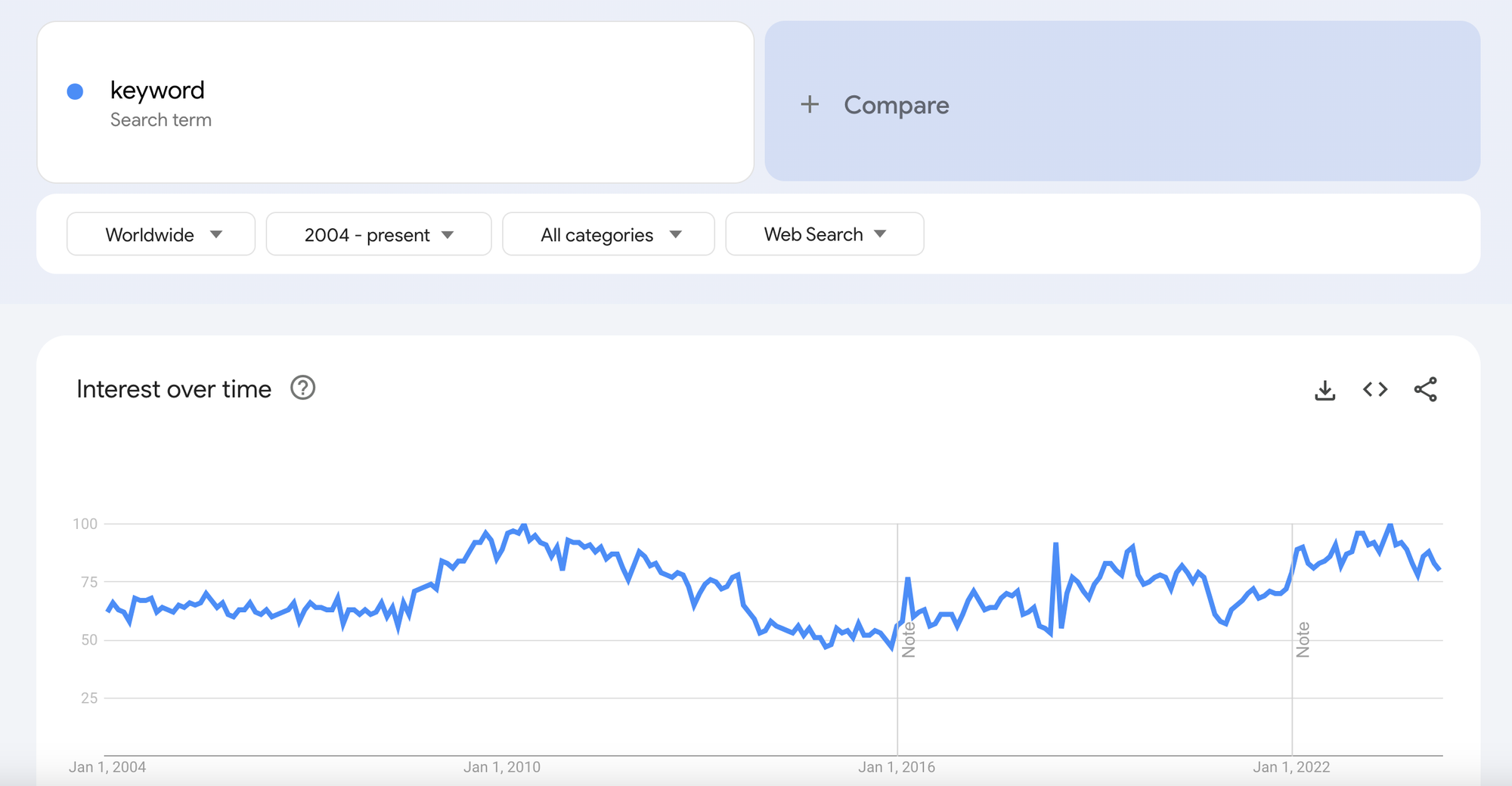

Keyword research documents compile hundreds or thousands of variations on keywords in a topic entity, listed next to their monthly search volumes. Research documents look something like this:

As I struggled through my first keyword maps, choosing between endless variations of how audiences searched, I recalled the taxonomy I’d invented at the image agency. At that time, I never bothered to consider who might be finding the image I was keywording. Now, I had information about what the searchers wanted — and it was completely different than I’d imagined.

I had to put myself in the shoes of the researcher who had questioned my keyword strategy at the image agency. I needed to consider:

- How would the content—whether image or webpage—be found?

- Who would be finding it, ideally?

- What words would they use to search for it, in a best-case scenario?

- If they searched on my chosen keyword, would they be satisfied if they found the webpage I’d chosen?

- If the best-case scenario keywords did not have high search volume according to the data, how would I choose a better keyword that still described the content on the page?

With appropriate research and a sitemap in hand, I had far more guidance on how to fill in the Keywords blank. Instead of guessing blindly based on one-sided information, I learned how to read the data.

How do you choose the right keywords for your content?

When I mentor folks with SEO training but minimal practical experience, I’m often asked: How do I choose the most appropriate keywords for my content? When I answer, I remember the researcher: consider who will be finding the results.

How do you choose the best keywords for your brand or a specific webpage? First, ask yourself all the questions above. Then, follow this process:

- Using the list of words in your keyword research, sort from the largest search volume to the smallest.

- Put yourself in the mind of the searcher. Start at the top of the list, then work your way down to the first keyword where you’d be pleased to find your website’s content if you were searching for that query. Don’t try to retrofit the content to the query. Pick the one that where the content that you have/are creating will best fit what the searcher wants to find with that query (aka the search intent).

- Ensure your chosen keyword is aligned with your brand language and page purpose. If it’s not, then keep moving down the list until you find the next best one.

- Keep going until your map includes all the topics for which you’d like to be discovered in search.

There’s no point in optimizing content for search if you’re not thinking about who’s going to find it when they need it most. It’s never about the most popular terms; it’s always about relevance to your audience.

Next week I’ll go deep on how focusing on topics instead of keywords is more relevant to a contemporary content strategy.

And in case you’re wondering: The image collection is apparently still in business, and their website is still powered by the same software that I used to first enter the photos and keywords. From the looks of LinkedIn, they hired a series of metadata specialists in the two decades following my departure, so I hope they fixed our initial non-system keyword approach. Really, I hope someone looked at those keywords and thought, “Did a crapulent college student write these?” Because the answer was yes.

Get more keyword selection guidance with our intermediate- and expert-level audience research course.

Hand-picked related content