This essay originally was published on June 22, 2023 with the email subject line "CT No. 172: Is all AI art terrible?"

Artists well known and obscure are experimenting with AI, both in galleries and in the sphere of media and entertainment. The public reaction to these experiments has been mixed, ranging from downright hostility to vast and remunerative acclaim.

Even among artists, sentiments about AI have been inconclusive. While some have rightly complained that their work is being stolen by generative AI tools which rehash their ideas at scale without paying for it, creative theft isn’t new. Their human peers steal and scale work, too. The difference is that humans can subtly compare and contrast style when borrowing whereas AI has no aesthetic or taste of its own aside from mimicry.

So when evaluating eccentric media that uses generative programs like Midjourney and Adobe Firefly to create art, it’s worth asking whether the artist is bending that eccentricity toward a particular end — something recognizable as funny, paradoxical, or outré — or lazily allowing the software to fill in the blanks. In terms of what is or isn’t accepted as art in the AI space, recent examples show that artists, but also corporations with investments in art, are still testing the waters and perhaps trying to line their pockets in the process.

Can AI bring John Lennon back from the dead?

Known professionally as Beeple, artist Mike Winkelmann has experimented with incorporating non-fungible tokens (NFTs) into his work, most notably in his video-sculpture hybrid HUMAN ONE, which sold at auction for nearly $29 million. Like many AI art generator programs do, though with less precision and on a much larger scale than Winklemann’s, the sculpture uses an NFT program to generate constantly changing images that it projects on its four walls, letting viewers watch as the work evolves over time.

Elsewhere, similar programs are being trained to extend an entire body of work. Tezuka Productions Company, the Japanese animation studio founded by acclaimed cartoonist-animator Osamu Tezuka in 1968 and now run by his son, Makoto Tezuka, revealed in June that it would be publishing a sequel to one of his comics, Black Jack, using ChatGPT-4. The prospect struck some fans of the late author as blasphemous.

As the Black Jack sequel shows, the aesthetic, ethical, and legal questions that arise from these AI-generated works are thorny. Consider the new Beatles track, announced by Paul McCartney the same week. Extrapolated from an existing demo containing recordings of John Lennon, the new track now has an AI approximation of Lennon’s voice — and McCartney’s blessing.

But is the new AI-powered song a Beatles’ song just because McCartney, who calls it “the last Beatles record,” says so? Can there be another Beatles album if half of the group is dead? The financial incentives informing the decision to make new, licensed Beatles songs are surely enormous, but they also seem to usurp the work of curators and archivists, and to ask the public to revise its assessment of an artist whose work has been understood as complete for 43 years. Moreover, is it respectful to the deceased artists who have no say in this unprecedented use of their likeness and creations?

These aren’t entirely new questions. In 2009, Random House published Vladimir Nabokov’s incomplete novel Laura against the late author’s express wishes. New versions of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis have resurfaced every few years because its copyright protection in the United States lapsed from 1953 until 1996, when it was reinstated until last year.

But in the cases of Tezuka and Lennon, rights holders are asking the broader public to accept a computer’s educated prediction based on the behavior of two legendarily inventive souls. Software can automate some of the processes of artistic generation — Winkelmann’s work makes that clear. But can it create or even meaningfully stand in for a living collaborator?

AI for what and whom

When looking at art that uses AI, it’s worth asking exactly where the AI was used, by whom, and to what end. Winklemann made a cheeky Beeple piece about these questions, GENERATIVE FILL, a digitally painted frame around a PNG checkerboard pattern that usually indicates empty space in image-making software like Adobe Illustrator. Winklemann’s point seems to be that whatever is generated and put into the center of the images is blank and, to an extent, meaningless. It’s art without an author, and centering it feels like centering a void.

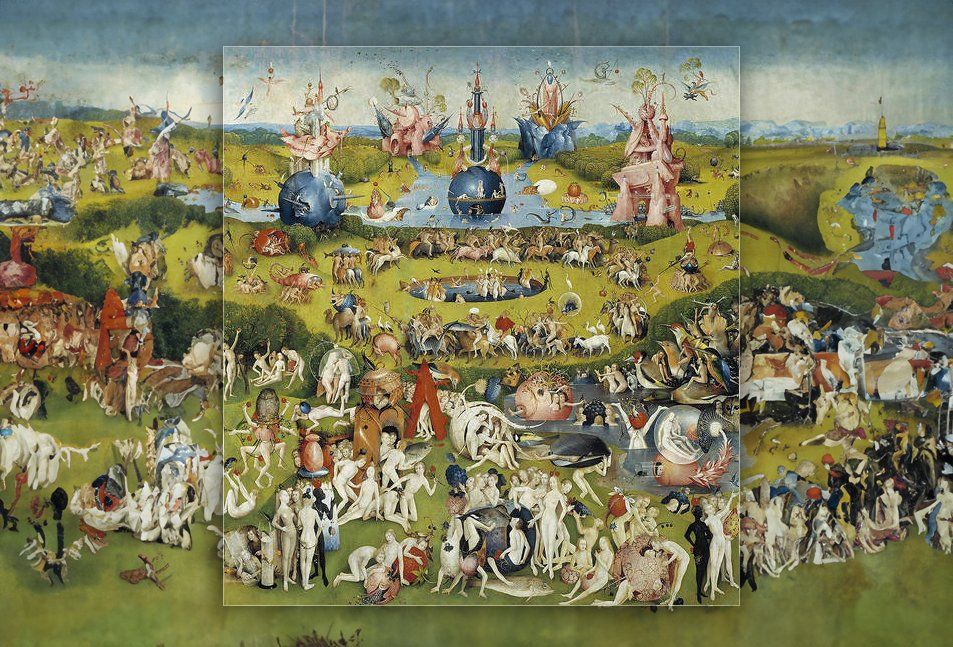

It turns out that void has a predictable appetite. Consider how AI booster Kody Young used Adobe Firefly’s generative fill tool to create images that extended the borders of famous paintings, including Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, and the center panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. When Young posted the images to social media, uproar ensued.

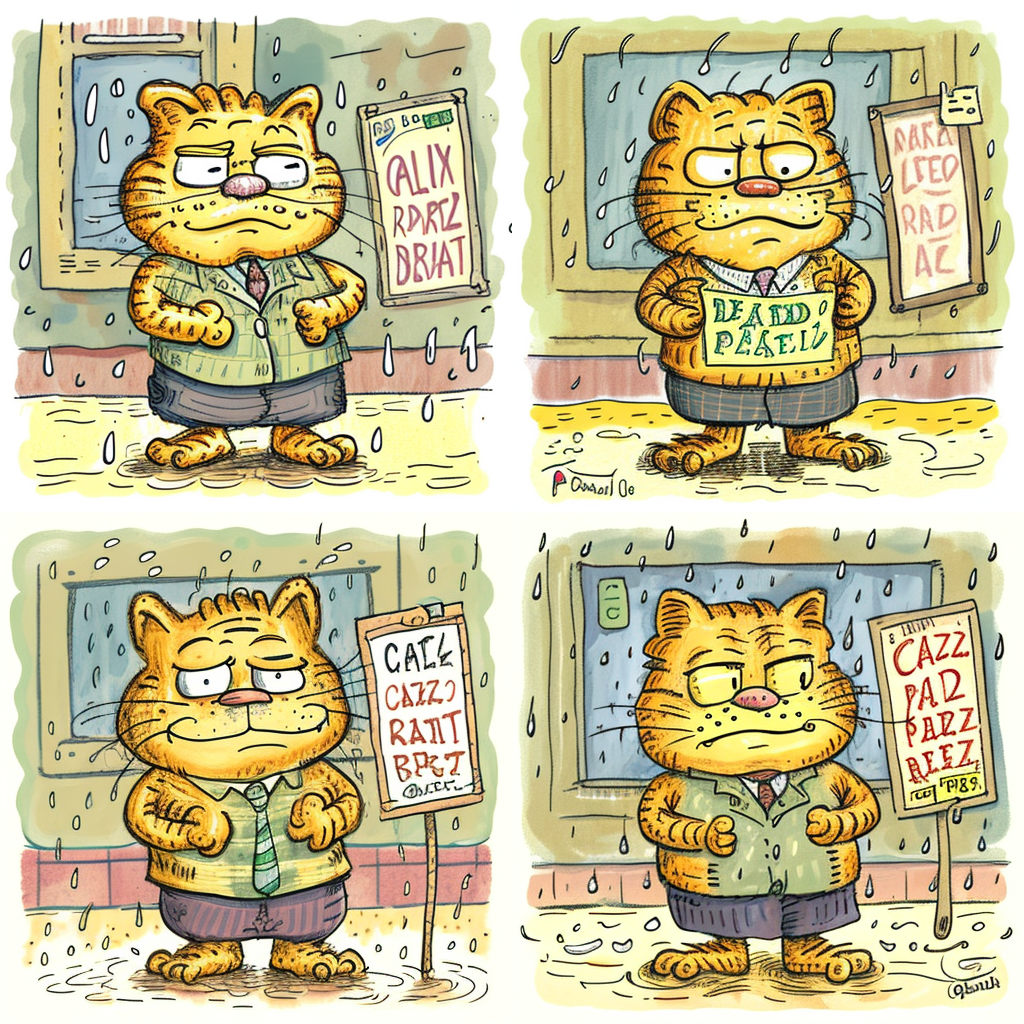

Young isn’t an artist, and like most AI boosterism, his results covered ground thoroughly colonized by professional illustrators. Plenty of artists have drawn inspiration from canonical artists like Bosch, da Vinci, and Michelangelo in their transformations that are worth considering. For example, cartoonist Sam Owen repopulated Bosch’s painting in the style of Garfield cartoonist Jim Davis and also drew Leonardo (Ninja Turtle, not Old Master) in a version of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. (As fans of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise may have assumed, the circle delimiting the reach of Leonardo’s multifarious limbs is a pizza).

Because he’s not a computer, Owen has a sense of humor — and a compelling one, too. In his Bosch recreation, he’s stripped down the “Hell” panel of The Garden so that a manageable number of the painting’s events remain, which lets him draw it at a scale closer to a Garfield strip than Bosch’s nightmarish vision. Then he uses colors exclusively sourced from the Garfield palette — oranges and yellows, purples and blues — and reduces all the shadows and textures to hard lines and crosshatching. The resulting image looks like a comic strip. In other words, Owen did the opposite of what the Firefly algorithm did: he made a significantly altered work sourced from the originals it parodies.

If Firefly retained the colors and the textures, but couldn’t grasp the form, then Owen looked at the painting and understood that a punchline-laden riff on it would duplicate only the placement of the most recognizable elements — the things that make you go, “Oh, it’s that giant egg from that Hell painting, I get it.” Having placed the legions of demonic Garfields torturing assorted Jon Arbuckles in the correct places, everything else could be tossed out without losing sight of the original, making the eccentric transformation a savvy one as well.

What interests me about these two competing approaches — AI pilot versus AI tool — is that they’re similar in concept, the process and results are worlds apart. Firefly’s idea of what might be happening beyond the edges of Bosch’s earthly garden is blobby and nonspecific. The program nearly gets the colors right, but it’s also merely extrapolating: the borders of the paintings are each a significant choice on the part of the artist, and simply matching the colors does little to suggest new choices a long-dead genius might have made.

Far more visually striking, though not heralded as the coming of the machine-artists at the time of its rollout, were the images Google made with its bizarre DeepDream crawler tool. (Here’s its Mona Lisa.) If anything, the new material looks like a cubist painting using the colors from Garden.

Software is a tool; tools require skill

Bosch’s original renderings are fascinating and disturbing precisely because they’re so realistic and detailed. Strangely, AI often comes up with Boschian variations when it’s trying to do realism — witness the many-fingered ladies and uncanny cats of AI short The Great Catsby. But when faced with Bosch himself, the computer falls short. To quote another artist, filmmaker Gaspar Noé, “If you’re going to copy someone, you have to do it better or funnier.”

The question, then, is how to use AI to express human eccentricity — not to mimic it, which seems to have less compelling results. To get a working answer, we ought to consider that computers are omnipresent in the recent history of human-made digital art, too.

Art software has traveled a long road since the late ’80s, when Microsoft introduced the glitchy flat colors of Paint — now an aesthetic all their own, popular with at least one member of the musical group mentioned above — on all of its Windows operating systems, and Apple developed the Newton, its original pen-and-pad computer. (It flopped.) In the 1990s, artists scoffed at “computer coloring,” which tended to mean over-application of gradient tools (something the computer wasn’t doing by itself). Back then, the illustration software that Owen and his artist peers use to create their work, like Procreate and Clip Studio Paint, would have been anathema. But attitudes toward digital art changed as the industry began to distinguish the good work from the bad.

Today, computer programs are often the only way that artists find paying work and using them competently is appropriately recognized as a valuable skill. For example, any mass-produced comic sold in a bookshop is colored using software. In fact, a computer program is sometimes the only way to duplicate newsprint colors with any fidelity.

Consider how comic book restorer José Villarrubia compares reproductions of Marvel Universe creator Jack Kirby’s drawings of the villainous giant Galactus. The first image is a scan of the original but aging print. In the center image, Villarrubia lovingly reproduces the colors himself. In the rightmost image, you can see how Marvel introduces garish tones that bounce off the fancy archival paper, rather than bleeding into cheap newsprint. It’s an example of the kind of work Villarrubia does professionally for DC Comics, where he gave the same white-glove treatment to a volume of comics by Bernie Wrightson (often Stephen King’s illustrator of choice). It’s work of profound expertise, useful in an industry where a delicate touch is vital, and it’s only possible with a practiced hand guiding the mouse.

That’s not to say that this kind of technology can’t be misused — there are looming legal pitfalls embedded in the language models trained to absorb as much of the public internet as possible. The first is for artists and creators themselves, who quite understandably don’t want to see their work replaced or reduced by sophisticated computer programs. The second is for larger corporate rights holders, who have already begun formally contacting tech companies and regulators with vague threats. A letter from the record industry lobbyists to the United States Trade Representative (USTR) was blunt: “To the extent these services, or their partners, are training their AI models using our members’ music, that use is unauthorized and infringes our members’ rights by making unauthorized copies of our members [sic] works.”

The rights of artists aren’t any less vital because some of their technical skills have grown obsolete. But the software that learns how to parse enormous volumes of data doesn’t necessarily have to be trained on other people’s copyrighted songs, movies, and JPGs. It can provide valuable insight at institutions with huge datasets, too — imagine a version of ChatGPT that could answer questions about historical trends in SEC filings, or in the use of color among 19th-century oil paintings.

Human art is made of mistakes, but high technology doesn’t prevent errors. Frequently, it reveals what makes errors so human and, too, why they hold our attention. Just as other art forms often experiment with the hard edges of technical capability — guitars with deliberate distortion, video art incorporating magnetic static — the trick with AI is not to force it to duplicate human technical capabilities, but to find its limits and exploit them. I can already count those limits on all seventeen of my AI-generated fingers.

Sam Thielman is a reporter and critic based in Brooklyn, New York. He has written widely on technology and business as a tech reporter at The Guardian’s business desk and as Tow Center editor at the Columbia Journalism Review. In 2017, he was a political consultant on Comedy Central’s sketch series The President Show. He currently edits Spencer Ackerman’s newsletter FOREVER WARS and writes about comics for The New Yorker.

Hand-picked related content