This essay originally was published on April 27, 2023, with the email subject line "CT No.165: Methodologies for evaluating long-term content impact."

Several years ago, I experienced one of the distinct privileges of working for a sexy Silicon Valley startup: I learned what it feels like to sit in a $20,000 office chair. Situated in one of many huddle rooms, this lounge chair was clearly meant to inspire amazing one-on-one jam sessions. I thought this chair might be a good fit in my living room, so I found the manufacturer and googled the price, and lo and behold: $20k. I was horrified. While it was comfortable enough, I didn’t feel much different than other chairs I’d sat in before, the ones that didn’t cost tens of thousands of dollars.

My employer’s offices were filled with these $20k chairs, and I immediately wondered, “Who approved this specific chair as a necessary use of the venture capital poured into this company? What even is $20,000 times however many chairs there are?”

Assessing the value of my office furnishings was a far cry from where I had been working a few months before, when I was a PhD student in evaluation and education technologies. There, I’d been seated in a dark, cave-like office with old desks and creaky chairs, hidden away from the rest of the department.

And while I’d left the musty furniture behind for a seat at the other end of the spectrum, I realized that my chosen field of PhD research had more relevance in my new role than I initially thought. Sitting atop those premium office furnishings, I realized that my work in the typically academic field of evaluation could benefit this shiny, bright workplace, especially given the chair’s price tag.

If you’ve worked in government, nonprofits or academia, you’ve likely heard of or participated in evaluation studies. Evaluation methodologies determine the merit or success of a particular program, department, or initiative based on predetermined success or criteria. While not legally binding, the process of evaluation ensures organizational resources affect their intended outcomes.

I decided to introduce evaluation to various teams at my company. Knowing that people dislike being held accountable when it threatens a comfortable status quo, I was prepared for a bumpy road. But the evaluation idea flew with many departments: my colleagues liked being held accountable and wanted to know they were doing good work that contributed to the company’s success and supported its mission.

Although a startup is technically accountable to venture capital firms doling out millions of dollars, a private company’s responsibility is to valuation and investors first … even when its activities directly impact the public. (In fact, U.S. corporations are legally liable to their shareholders before anyone or anything else, including their employees and customers.)

But when dealing with grants of, say, tens of thousands of dollars, nonprofit and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are held far more accountable. Because they are tax-exempt, they're scrutinized to ensure they follow the conditions for that exemption. Unlike chancey and expensive startup ventures, nonprofit programs are tightly monitored with rigorous evaluation programs. A hard-won $20,000 grant isn’t going to purchase a single office chair.*

Like nonprofits, private companies take money (and lots more of it at a time) and promise to create some impact. They promise to make a change. They get tax breaks, too. Evaluation determines if the activities of an entity matchup to the outcomes and impacts promised. More broadly, it uses the rigorous scientific methods favored by empirically minded businesses, but with the end goal of determining goodness or merit.

Increased accountability might be frightening to some, but evaluation should also have a place in private companies. Whatever regulation exists isn’t cutting it, especially considering recent rounds of mass layoffs and executive-level scandals that leave well-meaning employees without recourse.

Especially for content teams, who are often struggling to prove their value to a company’s bottom line, evaluation can be a life raft, another tool for creative teams who want to demonstrate their impact on the company’s performance. After all, if brands are going to invest in their mission, and employees are going to be vigorously screened for values-fit, the formal process of evaluation can keep us all accountable.

*Editor's note: I recently discovered that the highest honor in American letters, the Pulitzer Prize, is an award of only $15,000. Think about $20k startup chairs, think about the folks who received all that venture capital, and then consider the actual work of winning a Pulitzer Prize. —DC

Introducing evaluation: An approach to understanding long-term impact

Evaluation encompasses much more than heuristics. It handles abstraction and complexity more often and is also designed for the long term (aka, not quarterly or even annual reporting). Specifically, while UX heuristics can cover the specific user interface of a software, evaluation would determine whether the development and dissemination of the software had the intended outcome and impact on its customer base. Evaluation also highlights externalities, or unintended consequences of a project, whether they impact an ecosystem or audience.

Although the field has existed in some form since the 1930s, advocates of organized evaluation have focused energy on finding a place in academia (to train other evaluators) as well as resolving issues of professionalism and standards for practice. Only one well-known evaluator, Michael Scriven, has consistently asserted that evaluation should be reaching other sectors like private industry. No time like the present to heed the call.

So what does evaluation have to offer content teams? A good starting place is developing evaluation criteria, since it is most similar to those heuristics you’ve probably heard of, and then moving into another skill area called logic modeling. Let’s look at each in turn.

Accept all cookies: How to develop evaluation criteria

Developing evaluation criteria is a good first step because it can be done relatively quickly and in a short amount of time. If you already have heuristics or governance for your team’s outputs, like style guides, brand guidelines, and so on, start here. When was the last time you looked at them? Did you inherit them, and do you agree with them now? What assumptions went into their creation? How consistently are you using them? And how do they affect or impact the business, in your estimation?

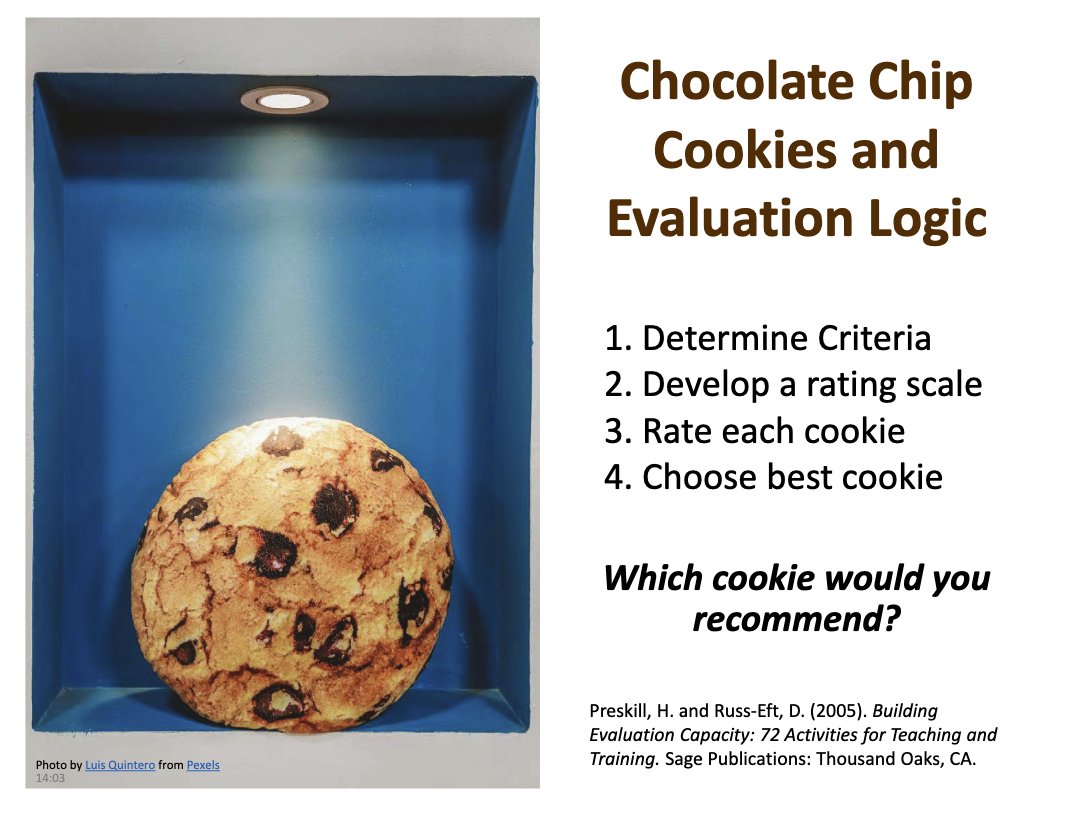

If you don’t have heuristics, or aren’t as familiar with them, be aware that creating criteria isn’t a straightforward skill. Many evaluators going through formal education programs to learn the “chocolate chip cookie” lesson to get to know the mechanics of developing criteria. Give it a try, if only as a team bonding exercise (or way to help others level up their skills in criteria creation and measurement; rating scales are also tricky):

- First, buy a few different kinds of cookies

- Get together in small groups or individually if your team isn’t very big, and define the indicators of “good” for a cookie (get ready for a lively conversation!)

- Develop your rating scale to measure each indicator

- Rate the cookies

- Choose the best one

Now that you have created evaluative criteria with cookies, try creating or updating heuristics for your team’s content and performance, following the same steps as you did with the cookies.

If you want to create criteria for something more abstract, that’s also on the table. For example, consider how to evaluate a whole content team that's grown rapidly within a short period. HR’s performance reviews evaluate each person individually, but what about the team’s overall cohesion? What other criteria would you look for in a good team?

Or maybe you’re trying to figure out how to prioritize competing demands from different domains like Sales and Product Management. Developing evaluation criteria to process those demands transparently and uniformly can go a long way to logically think through new requests and nurture your relationships with other teams.

The basics of logic modeling: Evaluating long-term impacts of content projects

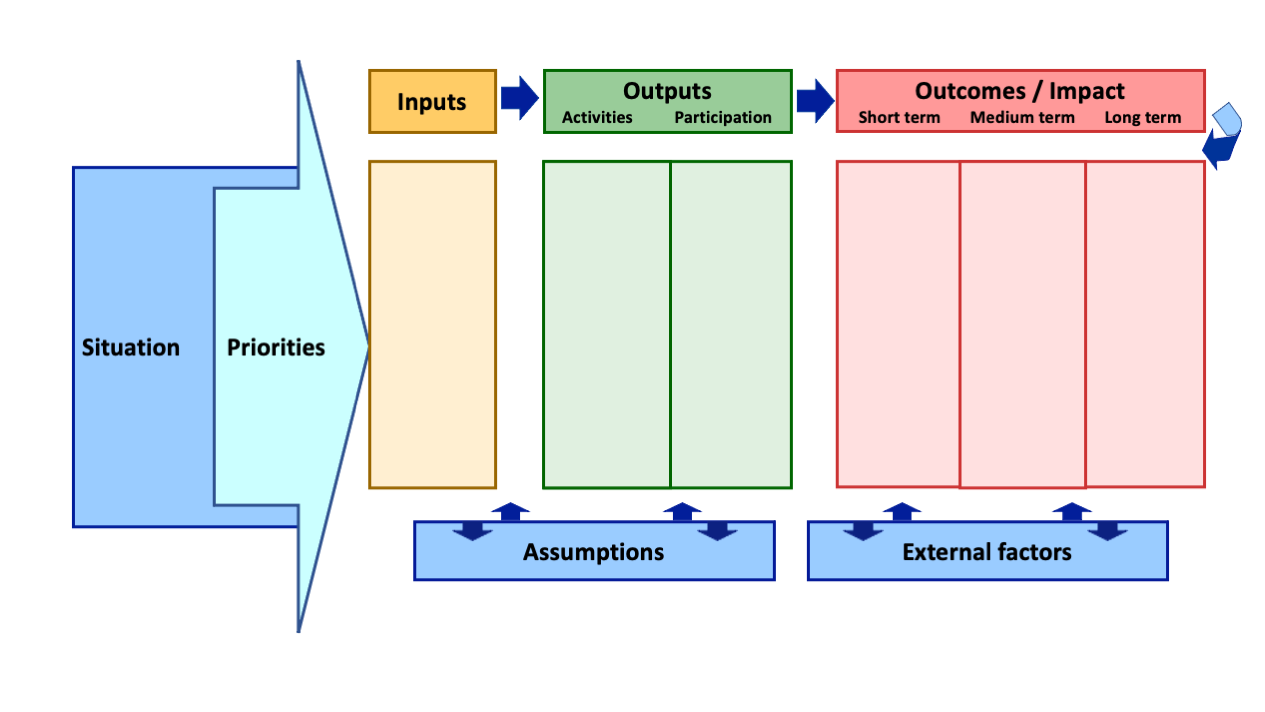

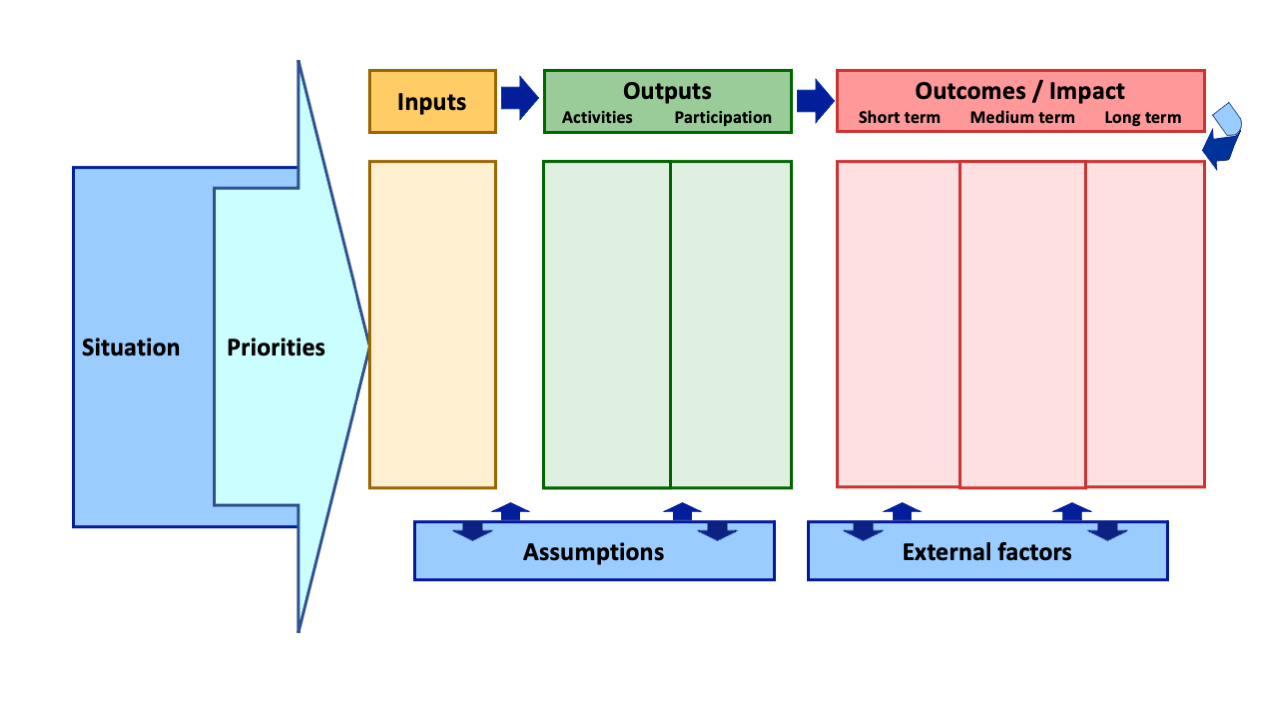

Another keystone of evaluation studies, logic modeling, is a more in-depth process. In logic modeling, stakeholders create a visual map that clearly shows cause and effect, explicitly surfaces and names assumptions, and goes further to identify expected outcomes and impacts of the work you’re doing.

From the discussion on evaluation criteria, you might think, “Right, well that’s why I have a style guide, branding, and so on, so that my content team knows what ‘good’ means when they create content.” Yes! True, and necessary. But those tools help you assess the goodness of your outputs, which is only one piece of the larger model.

You might also have your ways of determining whether everything is working smoothly. But when you can also visually trace your high quality outputs to outcomes and impacts—‚and also articulate assumptions and external factors—you’ve developed a compelling anchor for executives and other stakeholders to react to when they bring up questions of content’s function and success. You’ll also create a framework for holding your team to the quality of their outputs with those editorial tough questions. In fact, creating a logic model with those stakeholders is a good opportunity to go over assumptions and external factors together, realistically, in a focused setting – probably at a company retreat! Logic modeling is not an activity for a Friday afternoon.

The logic model, then, externalizes a lot of internally held knowledge and sets it up in a digestible, visual way for conversations about your work, your team, and ultimately the value you bring to the business.

In this model:

- The situation is what is prompting the logic modeling.

Example: Engagement with existing content has dropped significantly in the last two quarters. Or, the campaign budget is significantly changing. - Your priorities are the top points to respond to after analyzing the situation, and influence the outcomes you want.

Example: If you’re specifically focused on a specific campaign or product launch, or you want to focus on a core audience, here’s the space to note it. - Inputs are specific quantities of people, materials, and anything else that goes into your team’s efforts.

Example: The amount of hours that your team has per week, or the amount of existing content pieces you’d need to repurpose - The assumptions that interplay along the bottom are what influence your inputs and outputs. Assumptions aren’t givens. Until it actually happens, it’s an assumption, and influences how you model your inputs and outputs.

Example: One assumption might be, “we need to restructure our existing content,” or “we need more new content, and more frequently.” Assumptions might also be more utilitarian, like “we are hiring 2 new team members in the next month.” - Outputs are all the specific artifacts you and your team are responsible for.

Example: Activities might be “migrate all content to new CMS” or “create 2 new videos.” Participation identifies who is part of these activities, from both production and audience. - The Outcomes/Impact are where logic modeling takes a twist. An outcome is a direct result or benefit for the intended recipients of your work. (Aka, not traffic, not conversions, not anything that benefits you.) The impact is the more abstract consequence or wider effect in the long term.

Example: If your priority was to focus on your core audience, what is the ideal outcome for them? The impacts listed would then answer the question, “How will their condition change, socially, economically, environmentally, etc?” Don’t just note the positive gains and ignore any potential bad outcomes; the logic model is intended to consider all consequences, good and bad. - External factors are variables that you are outside your control but influence your outcomes and impacts.

Example: Maybe a video goes suddenly viral, which could alter your outcomes and impact. More seriously, maybe a pandemic wipes out economic activity for a while, nullifying any positive outcomes or diminishing impact.

**Other logic model templates exist, but I’m suggesting this one because it’s part of an open access text-based course for digging into the mechanics of what logic models are, why they’re helpful, and how to create one. (You do not have to enroll or go through the content in sequence! And if you’re interested in logic modeling, the course is very friendly to casual clicking-around and exploration of the course outline.)

The ultimate goal of evaluation methodologies

A confession: this introduction was going to be my PhD dissertation if I had stuck around academia. Shining a light on evaluation and introducing it to our corner of industry might possibly seem entirely new to you. Or, maybe you’ve seen it before. The closest manifestation that I’ve seen otherwise is evaluation of investing in private industry, but even that tends to be mainly “impact investing,” aka investment that's still tied closely to huge public endeavors like the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The goal for content teams and private companies more widely is to incorporate evaluation as a skillset to improve ways of working and accountability. Evaluation encompasses concrete actions and introduces more accountability to private companies whose products directly impact the public. If a content team adopts evaluation, they get the additional benefit of articulating impacts that are often missed in the weeds of digital metrics. If evaluation shows that some part of the team or process needs strengthening, it becomes proactively clear and actionable.

Logic modeling and developing evaluation criteria are small portals into the realm of evaluation. They represent a culture and communication shift, and they might take some time before you see results, but keep at it! Evaluation is a practice as well as a tool.

At the very least, please don’t buy $20,000 chairs to sit on while you brainstorm your impacts and outcomes.

Hand-picked related content