This essay originally was published on August 31, 2023, with the email subject line "CT No.182: Is 'federated' social worth it?"

It's difficult to look at the state of the contemporary internet without experiencing a smidge of informed despair. Search, social media, and even news are in a state of increasing “enshittification.” Beloved vlogging service TikTok, now overrun by crummier (but more monetizable) videos, stolen content, and irritating growth hacks, is the canary in the media coal mine. Perhaps that's why so many services are trumpeting a coming era of what the tech industry calls “federated” or “distributed” content, a concept at risk of becoming a buzzword. So when we say federated content, what do we even mean?

For a long time, the social media game trended toward models that could be scaled to accommodate massive groups, designed not only to connect individuals but also to compete with television and newspapers. As a result, companies like Facebook have data centers all over the world where they host content for billions of users.

But everything on Facebook is hosted on Facebook's servers and communicates using Facebook's proprietary software; that's not federation. Instead, it's the problem that federated networks are trying to fix.

Conceptually, federation refers to when different hosts — or instances of niche social networks — can communicate with each other. A host can be anything from a single computer to a network of computers where users log on to share photos, videos, and text, or even an online forum. Notably, where federation shines is among small but digitally connected groups.

Most small websites — or small social networks — don't need mass, global scale. With federated social networks, smaller operators can ideally reach interested audiences globally without server farms or proprietary software. There are a few snags, however, and federation clearly isn't for everyone.

It's complicated: Laws, hosts and protocols for global social networking

Even if Facebook's servers are in another country, the company is incorporated on US soil and is still subject to US law (at least in the opinion of stateside lawmakers), along with growing global regulations. But as far as end users are concerned, they're all subject to Facebook's rules, not to their country's, when posting content.

No matter where they are, Facebook users are swimming in the same pool as all other users and connected hosts. For the average social media-ite who wants access to platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok, this arrangement is either assumed or ignored because it doesn't directly affect their daily media consumption and posting.

But on microblogging platform Mastodon, which uses a federated system, users must pick a host, often with its own quirks and rules, before creating an account. Ideally, those committed to posting on a specific host should consider factors like where the host is located, especially because copyright regulation, freedom of speech, and privacy laws can vary tremendously from place to place. (Such policies can also conflict with each other.) That host will be responsible for managing the content its users post, and those users will have quicker “local” access to other people who have also chosen that host.

It's a simplification, but it may be helpful to think of these federated hosts as neighborhoods. Or, if they're run like annoying fiefdoms, homeowners associations. Mastodon hosts collectively form a broader service, all united by a protocol called ActivityPub — a suite of software you install on your server that allows your instance to speak with other hosts also using the platform. If you wanted to host your own social network that is subject to rules made by you, not X or Meta, you could create your own Mastodon server on a single computer, or set of computers.

Another service, Bluesky, uses a newer standard called AT Protocol, which differs substantially from Mastodon in that it allows users more portability. In other words, if a user wants to change from one host (or “instance”) to another and still retain all their selfies, political musings, and memes, they're able to. AT Protocol also allows users to make their own instances. But the protocol isn't open to other hosts yet, so Bluesky launched as a centralized, rather than federated, system. Its strategy appears to be to attract a user base and brand recognition that can then be funneled into federated instances.

Silicon Valley's mogul class are hedging their bets, too. A third standard, Nostr, is making a similar play for users, with backing from Twitter founder and Bluesky board member Jack Dorsey. Web software giant Automattic, known for its WordPress content management system as well as publications like Longreads and The Atavist, has thrown its weight behind ActivityPub.

As with all social media platforms, the cultures of these federated services and the connotations associated with choosing a service or protocol vary widely. Mastodon users are often open source tech geeks. Bluesky's users tend to be pretty quirky and cliquish (the flagship instance is still closed, and many of the early invites went to Twitter addicts). While Bluesky is still centrally hosted, the dream of its eventual federation means that individual hosts on the service will be able to dictate their own rules and moderation systems. Compare this community to what's happening with X, where the rules are seemingly dictated directly by owner Elon Musk, who has promised to end users' ability to block accounts and recently ordered an account reinstated after it was banned for posting an image of a small child being abused.

Much debate on Mastodon focuses on the utility of content warnings, in part because of federation. What if something you post on instance of Mastodon is something that violates terms of use on another host? What if it's still protected by the stricter copyright laws of another country, where some of your followers are hosted? As with any online community, individual hosts are trying to parse these thorny questions without the infinite cash and enormous legal representation that lets Facebook essentially make its own laws.

The Esperanto solution: Will federation actually fix social media?

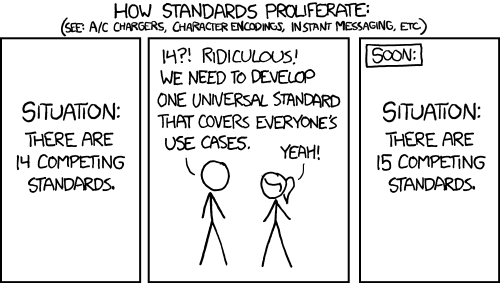

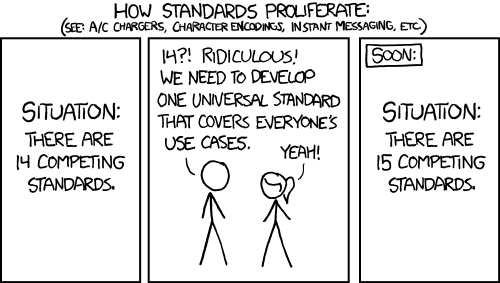

The most obvious problem with the brave new world of federated and distributed networks was articulated years ago by Randall Munroe in his prescient webcomic xkcd. In “Situation,” Munroe writes: “There are 14 competing standards.” “14?!” one stick figure says. “That's ridiculous! We need to develop one universal standard that covers everyone's use cases.” “Situation,” reads the final panel: “There are 15 competing standards.”

Think of these groups as miniature governments competing with one another for land rights and trying to attract talented people to their region without ceding too much power to those newcomers. On the one hand, ActivityPub partisans are annoyed that AT Protocol's developers didn't try to work within the existing community of ActivityPub contributors to improve the existing standard.

On the other hand, AT Protocol's FAQ blames the disjunct on a fundamental disagreement about what a universal protocol ought to look like. This might look like petty squabbling between tech geeks who want to boss each other around — and it's probably more than a little bit of that — but given the growing mass of dissatisfied netizens, there's now a huge opportunity to build (or reacquire) a user base that is drifting ambiently around between platforms. New protocols and services may not ultimately capture this wandering audience, but their development can allow communities to build their own digital habitats.

That brings us to monetization, which in many cases just means advertising. Instead of charging users a subscription fee for access, Bluesky will almost certainly incorporate advertising at some point and try to carve off some of Twitter's declining share. Even in its heyday, Twitter was a great place to distribute content, but a rocky place to advertise — unless you were trying to reach the venture capitalists with deep pockets who hung out there.*

As silly as the debate over competing standards may seem, the dream is an inspiring one. Imagine a world where nobody has to deal with the headache of monitoring a community of users that numbers in the tens of millions, where the communities themselves have scaled down to a more manageable level and can speak to one another.

AT Protocol and ActivityPub aspire to be trade languages, and the individual social networks they create become digital communities. It's important to recognize that these protocols aren’t blank slates and that financial and social incentives are at play in their development.

But they represent a way for people to curate smaller, more manageable communities. There are things Mastodon can't — or won't — do, and long discussions about whether or not it ought to do those things. But it is designed to be customizable, and if you want a feature for your particular instance, you can make the case before the Council of Federated Nerds.

*How advertising would play out across a federated network is unclear. Would Bluesky act as Google does with the larger web, monopolizing attention while taking a cut from both publishers and advertisers who use its ad networks? I have many questions.

Against compression: Viewing social media assets in full resolution

Organizations may find significant advantages to the brave new world of decentralized social media. Chief among those advantages is the opportunity to start networks of your own, either single-handedly or in consortium with like-minded businesses. A museum could start a photo-sharing instance on AT Protocol or ActivityPub that satisfies license requirements for the display of its paintings and sculptures; it could also host uncompressed photos of its works to highlight the difference between paintings and digital art.

And that museum's federated social network instance could also integrate content in its feed featuring newer work from contemporary artists hosted on other instances, as long as they follow the same licensing and quality protocols. This interoperability between hosts is a key feature of federated social: Hosts can make their own rules and only integrate content from other hosts that also follow those quality control rules.

Currently, the state of compressed media on global social networks remains abysmal, since mass social networks prioritize audience growth and engagement over content quality. Twitter and Facebook crush digital images down to manageable formats. Flickr is one of the few services that retains them at their original resolution with licensing settings, but those Creative Commons licenses are more like guidelines and don't protect professional photographers from having a quick right-click-save-repost-wtihout-credit by unscrupulous internet publishers.

But compression settings can be changed on individual Mastodon instances to allow for larger or smaller images, and, potentially, the addition of enforceable licensing agreements.* The alt-text function could include valuable information about the work and the artist, like a museum didactic. Requests for reproduction licenses could list the url of the Mastodon instance hosted locally, making it part of the museum's own suite of software, but remain accessible to other Mastodon users within their own instances.

*Licensing agreements and Mastodon loopholes are clearly still up for debate, but we're describing the dream of the Fediverse, not the current reality.

Mondrian 3.0: Content fidelity and digital representation

Federated rules mean that content quality standards can be maintained by each host, rather than compressed into mass social network formats. In 2010s social media, development protocols dictated the way media and text are displayed on the web. We've gotten used to seeing heavily compressed video instantly but never looking at a high-resolution picture of a work of art. That could change depending on your (or my) art-focused social instance.

Our phones are compression machines — handheld devices for giving everything to us at a diminished size and quality. But they don't have to be. They could be little windows into much larger worlds, rather than sardine cans full of every possible different kind of material, some of which we want and most of which we don’t.

For example, a Mondrian might look like a raster image when displayed in its entirety in the glass rectangle of a phone, but when it's displayed at 5 megapixels, users will be able to zoom in and see details, where it becomes clearest how skillfully and painstakingly the image is painted. Instead of content, the end user sees craft.

One of the most popular images on the web remains Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights; it is mixed and remixed practically daily by interested, amused art lovers. That's because its details are obviously in need of magnification and exploration. It's possible to design a protocol that shows how thoroughly this is true of every great work — the impasto on a Van Gogh, the scope of a Manet. The rectangle can be a microscope, too.

This is only the tip of the iceberg. Authentication protocols like OAuth can be made to work hand-in-hand with social networks. Libraries could run entire networks using open protocols, allowing social users to bind their library cards to identities on those protocols and virtually check out books, the way the Internet Archive does for its users. User privacy can be maintained by divorcing user identifiers from location information or personally identifying info, just the way the US public library system works. Imagine seeing your library's new releases in a feed and nabbing the one you want for your tablet as soon as it comes out.

No logo: It's the software, not the brand name

These federated social media instances would not conform to the kinds of standards that growth-oriented tech companies prefer, in which rapidly loading “personalized” algorithmic feeds require compression to serve immediate content. Mass social networks overtake both the creator's preference for how artwork should be seen and the user's preference for what they'd most like to see. In the ideals of the Fediverse, the reverse chronological curated feed returns, giving more power to both hosts and end users to display the content how they want, and to whom they want, while still remaining globally networked.

By design, fedested social networks more directly serve the user, and thus attract users who would receive significant utility from their specialized protocols. In theory, anyway. Part of the appeal of Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok and Twitter is the low level of technical know-how required to use them, thus the ubiquity of all your high-school friends or fun coworkers. People are there because people are there. Adoption of federated networks is currently slow among the general public, partly because it's so hard to find a thriving individual network on the Fediverse unless it's connected to an existing audience. Mastodon's “Pick a server” is a big roadblock for people used to choosing a username and password and then logging on. As all end users know, it's hard to tear yourself away from the main feed when it just keeps serving up that quick-loading content.

But for mission-driven organizations or brand publishers that want to invest in cultivating a niche, decentralized online community, these federated social networks may engage audiences more deeply. They could lead to a future where community managers are less worried about algorithm changes they can't control and more worried about content quality. Publishers hosting federated networks could discover global audiences without having to pay to boost posts.

And if the public can get on board, the tech-utopian dream of a public, neutral internet could be within reach. At the very least, federated social networks could mean more control over content quality and a way to communicate with audiences around the globe without the trappings of ad-supported algorithms. As it stands today, one of the web's largest problems is that it has been reduced to Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. Even if a new crop of federated websites doesn’t immediately attract massive user share from those ungovernable giants, the potential for increased diversity has a lot to recommend it.

Sam Thielman is a reporter and critic based in Brooklyn, New York. He has written widely on technology and business as a tech reporter at The Guardian's business desk and as Tow Center editor at the Columbia Journalism Review. In 2017, he was a political consultant on Comedy Central's sketch series The President Show. He currently edits Spencer Ackerman's newsletter FOREVER WARS and writes about comics for The New Yorker.

Hand-picked related content