This essay originally was published on February 2, 2023, with the email subject line "CT No. 153: PhD, meet the UX research industry."

Solar panel installation seems like a harmless topic, right? While conducting UX research for an energy company, I started with easy questions like, “When were the panels installed at your house?” At least I thought they were easy.

Instead, one of my study participants broke down bawling while trying to answer. Apparently the house had previously belonged to the interviewee’s recently deceased father. My instinct said to stop the conversation immediately, especially because two other non-participants were present: my notetaker and my participant’s concerned, increasingly angry, family member.

This instinct came from over a decade of human research in pharmaceutical trials and PhD training. Both have strict protocols on how to protect a participant in a study, which are drilled into the researcher. If something goes wrong, there are clear processes dictating how to safely handle the emergency. In other words, I had both the ability to manage this random emergency and the understanding that there could be serious consequences if I mismanaged it.

I calmly stopped the conversation, asked if the participant was okay, and then took off my researcher hat. I gently commented, “I can tell your father’s passing still really hurts and I’m so sorry I triggered more pain.” Glancing briefly at the family member I continued, “As a reminder, you are well within your right to stop participating, and we will leave immediately. You are never obligated to do anything.” Then I waited in my seat, patiently holding space for my participant, just present.

After a few beats, the interviewee said they wanted to continue because they felt we really cared. Other researchers might not be as patient, rushing through questions or treating interviews as an extraction. We were lucky; without this person we would have scrambled to meet the promised sample size in the given time budget.

As my UX career has progressed I’ve seen a greater emphasis placed on concepts like “human centered design,” which means more talking to people, more often. In recent years, the field of user experience has become more specialized, breaking research into a distinct role and making the kind of interaction I encountered more likely.

What is UX research in practice?

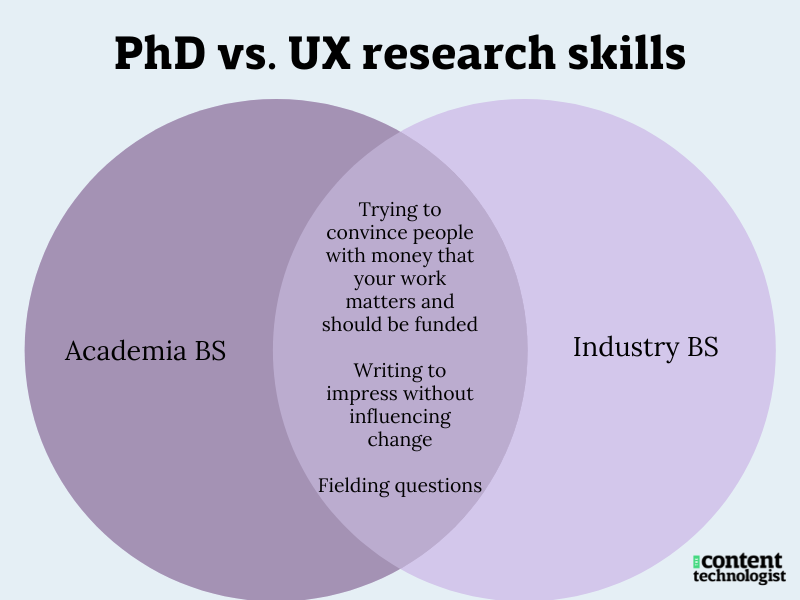

UX researchers interrogate topics as detailed as product feature interactions and as broad as strategic questions like, “Who do we really serve?” or “Should we make this product?” The breadth of topics seems ideal for PhD holders, who are increasingly joining corporate environments via UX research, changing the balance of academic versus professional backgrounds in teams.

Academia expats and full-fledged PhDs arrive at startups and enterprise companies alike amid increasing ethical and regulatory scrutiny of the tech industry as a whole. After the world of long-standing research universities backed by long-term endowments and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) overseeing every study, PhDs often experience culture shock in the rapid-growth, venture-capital-backed business world where it’s okay to “move fast and break things.” The credentials impress companies who seek PhD holders, but stakeholders are not necessarily prepared for the deep questions, increased scrutiny of methodology, and outcomes during quarterly reporting.

All in all, it’s a good time to talk about accountability in UX and the stark differences between academic and corporate environments.

At first glance, formal backgrounds in research ethics and training seem good! But consensus of what UX entails and expectations for research roles vary by company and team.

My PhD training and previous human research experience once got me into trouble during a large, high-profile project. I thought I had enthusiastic support but learned that my insistence on accurate research methods came across as “too slow” and “stubborn.” When a new manager explained that academic scientific skills do not necessarily map to industry, I realized having PhD training is only a first step toward executing UX research at a large corporation.

UX managers and directors, especially those with more traditional corporate backgrounds, should appreciate the differences between “industry” and “academic background” UX researchers before hiring both types into one team.

Once successfully integrated, UX leaders can use their team members’ seemingly disparate skills to set up accountability standards that emphasize respect for human subjects, above all, while supporting researchers in designing, executing, and reporting on studies.

What PhD students learn in academia

A person with a PhD has proven that they can conduct science as it’s understood in the university system. PhDs understand the current ethical standards of researching human subjects and are deeply familiar with the work in their chosen field. They’re also smart enough to contribute something new through the slow process of peer review and academic publishing. Regularly.

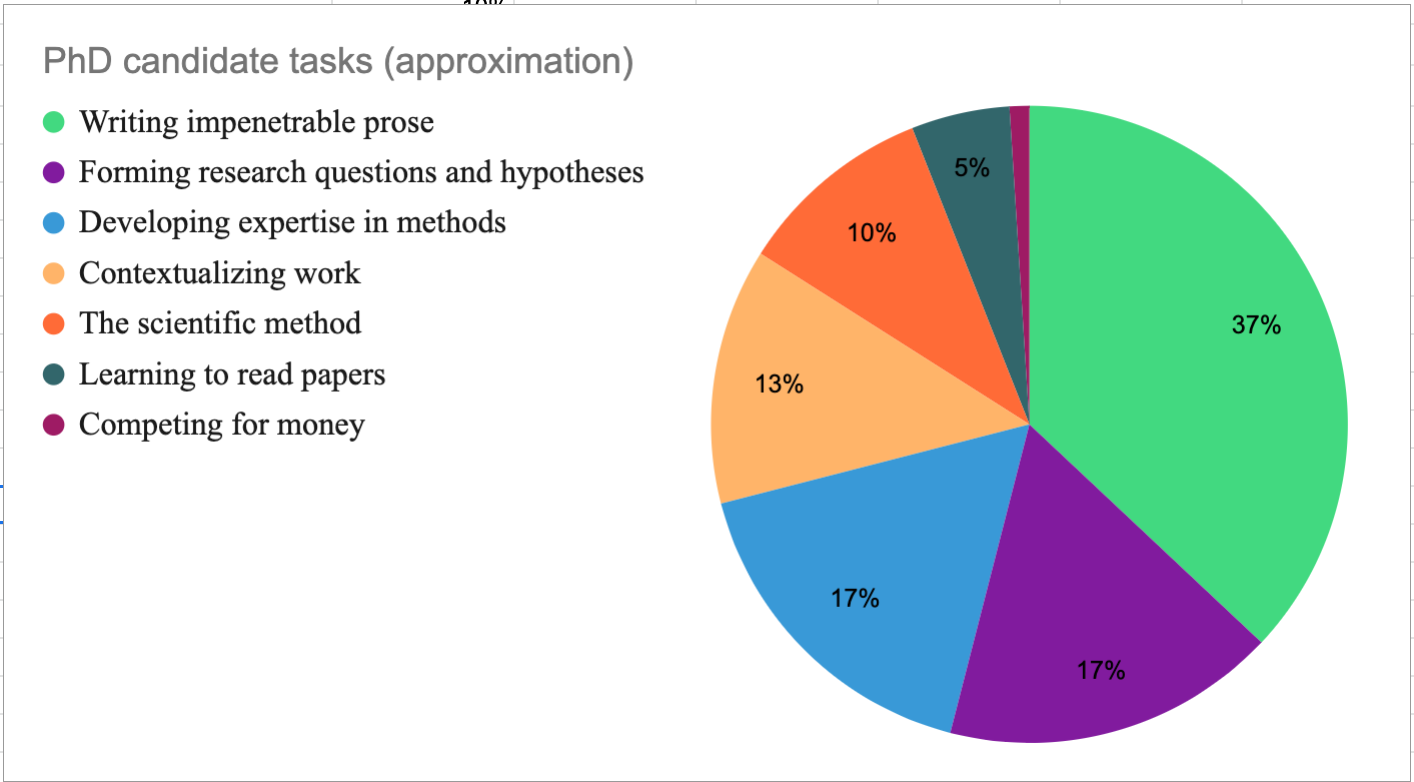

The real skills this person acquires during their approximately gajillion years of study include:

- Understanding and executing the scientific method

- Forming research questions and hypotheses, which are distinct

- Developing expertise in qualitative and quantitative research methodology

- Learning to read impenetrable research papers

- Contextualizing work, aka learning everything ever written about your field and therefore how exactly you’re going to be different and amazing

- Writing impenetrable prose yourself that sounds impressive enough to be published three years from now in a scientific journal

- Competing for grants, scholarships, and other institutional funding for your research

PhD candidates also learn to function on literal hunger because they’re getting paid subsistence wages even as adults with — ahem — college degrees. High salaries in tech are an attractive way to apply skills and make up for lost earned income while in school.

Everyone in this reality is behaving exactly as they should, given the system in which they’re operating: PhD students play the Hunger Games version of college while also ingratiating themselves with time-starved professors who may or may not be working in their best interests.

And professors need to manage their student advisees, balance teaching loads, and publish as frequently as possible to get tenure. They must keep track of deadlines like monthly IRB reviews, support students with any IRB-requested revisions, and then manage their students doing their research. If something goes wrong, the professor is held accountable.

Above all, everything in academia moves slower than a sloth on a scorching day in a vat of molasses. At no point does a PhD researcher work anything close to the pace of an agile software development team at a corporation. But accountability for one’s work is drilled in, internalized, and practiced. Research is about conducting scientific discovery, and if people get hurt in the process, the work will be in violation of university ethics codes and sometimes the law.

What a UX researcher’s role entails

UX as a field has never articulated, legally or otherwise, a specific set of skills or competencies. There’s no licensing board or Hippocratic oath. Job descriptions and requirements vary among companies and teams. Common practical skills required of individual contributors day to day can include: