This July, The Content Technologist celebrates five years of publication. If this newsletter helps you with your work or with your thinking about anything related to digital content, I would love to hear from you. I'll be publishing some testimonials in the anniversary issue on July 25.

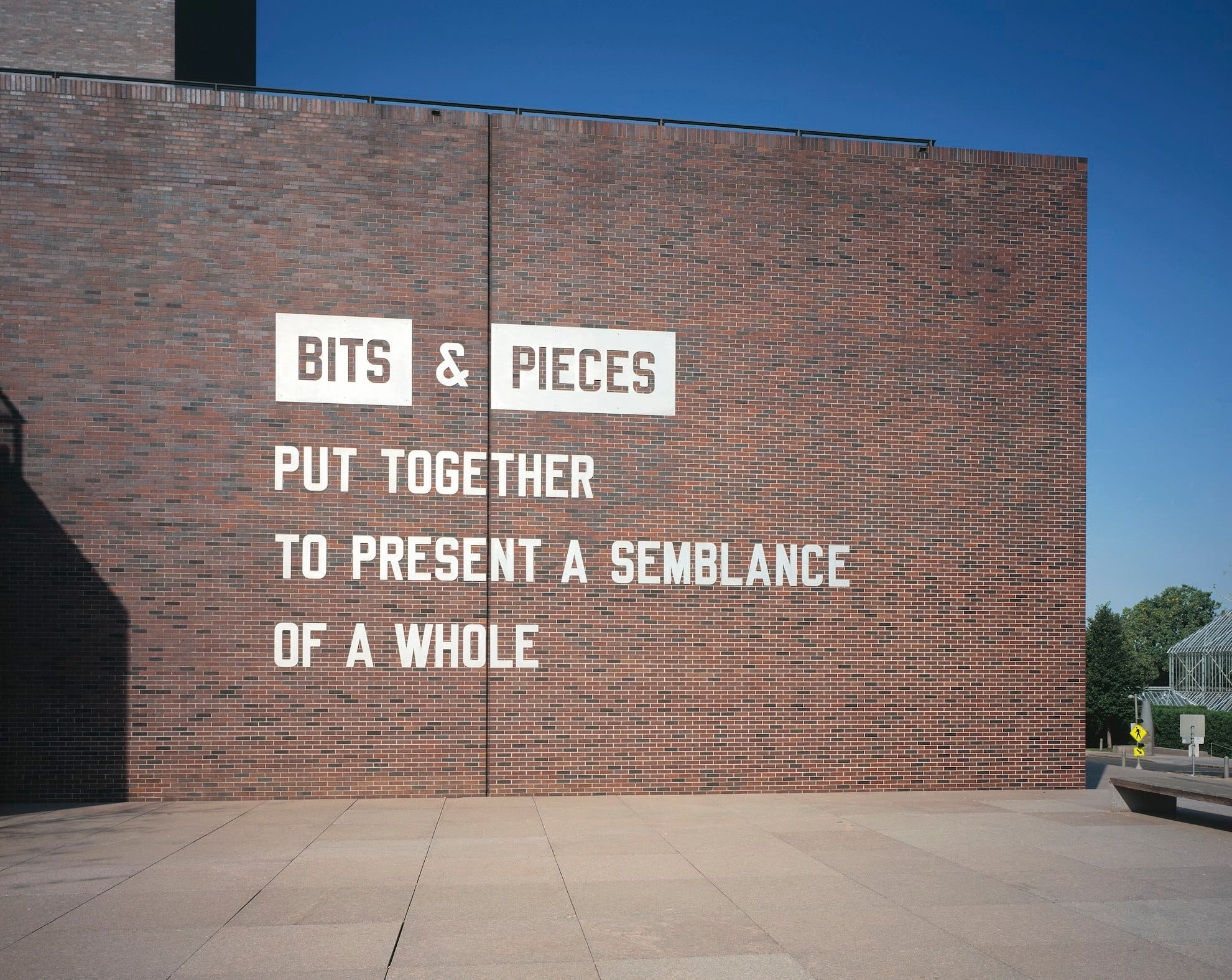

The Gestalt meets continuous optimization: Full of wholes > full of holes

If you've ever taken a psychology or design class, it's likely you've come across the theory of Gestalt: that humans see the whole as more than the sum of its parts. Gestalt theory underlies much of the perfectionism imbued in 20th century media and news production: even one error will distract from the meaning of the whole.

We edit and proofread and review with specially trained teams who understand the nuances of specific dimensions of production, because what we print is in part of some larger "public record." Because, when creating anything, "fixing it in post" is expensive. Because we know that if we overrepresent or underrepresent certain ideas, they can have dramatic social consequences.

Gestalt psychology underlies the study of perception and the idea that how an audience reads media as a whole is more important than the individual factors how it is made. To put it in business terms, it doesn't matter how well or efficiently your content workflow is designed because no one ever sees it; it matters how customers perceive the output of your product and your brand. The Gestalt, or the whole, is the brand, not the individual post.

Getting it right the first time: Gestalt in 20th century media production

When it comes to writing, thinking in wholes and Gestalts is easy for many of us because of how we were taught. Unless schools have radically departed from the system I grew up in, in most educational systems, a student's assignment is assumed to be 100% correct until errors are spotted. Each error detracts from the whole.

Even though your writing assignment may contain zero factual errors and immense creativity in problem solving, it's still graded as a 60% because of all the spelling and grammar errors. Or, conversely, you may have produced a 100% technically correct piece of writing, but if the ideas contained within are derivative, foolish, illogical, or plagiarized, you may still end up with a 60% grade.

Of course, the business of cultural media production does not run on the same rules as our educational systems. We are not graded on correctness, but instead evaluated on the monetary value of business output. Well... until someone notices that the business output is incorrect.

From my experience, humans notice errors before they absorb meaning, especially when asked to review content for publication. Those who are eager to correct will negate new information if it's presented even with a single error. How many of us have been excoriated by a superior or a reader for a small human error like a typo when the whole deliverable was original, effective, and otherwise effectively executed? People who have no experience in production don't know what goes into making information correct, engaging, and focused.

What's wrong with Gestalt thinking? In 20th century news, it certainly led to the belief that information produced and vetted almost entirely by white men was the source of all truth and knowledge.** Gestalt hides decision-making and collaboration behind a veneer of a united truth that has no attachment to the commerce behind it. If the inputs to the whole are not considerate of diverse perspectives, the truth of the whole may be null and void.

*Lots of research on the history of the history sexism and racism at newspapers remains buried in my master's thesis lit review. But IIRC, until fairly recently (the 70s and 80s), women reporters were rarely allowed to contribute to anything but the Style or Variety sections of the newspaper.

90% of the way there: Software development and "continuous optimization"

In media, if you want to distribute a 90%-there product, like a 90% movie, it would likely be considered a B-movie, not suitable for any wide release. But in tech, if a company releases software that's meeting customer needs 90% of the time, that appears to be acceptable in many cases, because tech companies believe they will later make up that extra 10%, usually by leaning too heavily on requests for new features instead of completing the half-done ones.

Gestalt does not appear to be a consideration in DevOps, the corporate tech methodology for continuous software builds that, in my opinion, degrades quality of life and product. Continuous optimization leaves one feeling always pressured to meet the next goalpost, leaving minimal time for reflection on the whole.

I've written before that the iterative approach and minimum viable product processes clash with both how media industries operate and how people read and internalize content. In tech, a company can release a half-done piece of software and convince customers it will grow and change for the better. Consumer trust shifts to the company and the brand and its grand visions to add fix the future, not the current state of the product.

Considering that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts is anathema for many digital marketers, search engine optimization experts, conversion rate optimization experts, advertising tech companies, or user research professionals. Empiricists — who often believe that what they are doing is "scientific"— hold the belief that isolating and testing individual variables is more effective than looking at the product from a holistic perspective. If we can identify and test one factor, we can gradually make improvements to the whole.

Never mind that the variables change constantly based on personal preference and personalization algorithms and culture and tech and auctions and algorithms and search terms and everything else. The persistent illusion of piecemeal optimization remains: If we identify the single phrase that infects mindless audiences with the urge to smash the Checkout button, we will rid our brand of all underperforming language forever. If we can tickle the part of the website that makes Google happy, our traffic will go through the roof.

If you've ever worked with someone obsessed with ranking factors and their recent drop in SEO traffic, someone who can't see the difference between their work and "good content," you know this approach of corrective minutiae is deeply imprecise. Optimizing factor-by-factor makes a website seem more machine than human.** And from a business perspective, incremental content optimization at the expense of Gestalt is a radically wasteful approach to branding.

People interpret a product or brand as a whole, and the more you make edits or change the meaning, the less stable the Gestalt appears. It is much more efficient to look at the whole as a representation of the sum of its parts than to optimize for incremental gains.

And because there are no U.S. truth-in-advertising laws for digital products, software marketing often has very little connection with the product itself, which complicates holistic perceptions of tech even more. Because the tech industry purports to be "scientifically testing" engineered content, the belief is that the technology will be perfect "soon." Google AI overviews will get better soon. ChatGPT will stop hallucinating soon. It's not perfect, but it's 90% there! The improvements promised in the commercials are just around the corner.

This Adobe commercial depicts generative AI functioning in Photoshop in a way that does not represent the actual experience of using generative AI in Photoshop. Photoshop's gen AI does not work this well and this seamlessly.

Tech companies in the business of generating content—whether for marketing, customer service, or just plain publishing information—need to consider how sophisticated researchers (and not just easy leads) perceive their company as a whole.

And software websites don't just need to be "there"; they need to be contributing to the positive holistic interpretation of the brand, from both human readers and, increasingly, natural language processing systems.

**Anecdotally, most websites affected by recent Google algorithm updates seem to have been taking this factor-by-factor approach to optimization, rather than optimizing for the Gestalt. For example, title tags would be well optimized for a single keyword, while invasive ad units would sit between every 100 words. Or product review websites were optimized for the search spam signifiers "best" and "vs" without regard to whether those navigational labels made to website visitors who didn't arrive from search.

The Gestalt of this publication

Anyway... I've been writing this essay all day, and I can't quite get to the Gestalt of it in a way that doesn't seem forced. That's the other problem with continuous publication and optimization: one feels like they always have to be creating new, and it is challenging to create a 100% there piece of content on such a rapid production cycle.

And yet. As of this month I've been writing The Content Technologist newsletter weekly for five years. The business and the project evolved over time: I've brought in outside writers and editors and collaborators. I've made pillars and built in public. At first I published software reviews in every issue, then once a month, then not at all. I've written long essays, longer essays, two-parters, manifestos, and rants.

It's all collected on a website, in newsletters, in notes and client deliverables on the Google Drive, and in my head. It's in an Airtable that has every piece of software I've ever evaluated over the course of five years. It's in a half-done CRM where I keep records of the people I meet with, but have trouble following up with because I'm awkward and not disciplined in sales. The pieces are there, or more than 90% there.

But at this moment, I have no sense of my publication's Gestalt. What does it all mean to me, besides the source of my business? If I were trying to evaluate my website as one would a manuscript, can I link together the chapters and recurring themes and big ideas? Could I turn all this content into a manuscript? Or an app? How could it be used to better support the small community of content professionals I reach?

My goal for the second half of this year: Wrangle the digital detritus of my brain and business back into something that resembles a cohesive publication. Get these 200+ newsletters into some kind of searchable, structurally sound state. Tie up the loose ends polish the rough spots. Finish the four courses I've been creating. And reevaluate how what I've made for the past five years fits into where I want to be in the next five.

It's time to take my own medicine, get out the red pen, and look at the business as a whole. Get the Gestalt in order. Spend some time pulling everything together to draw some conclusions. Ensure my in-line links work. Make sure the topics connect well and content is indexed meaningfully.

For the rest of this month, I'm celebrating five years of The Content Technologist, reviewing early issues, and making some plans for the future. And by the end of this calendar year, hopefully I'll have a sense of the meaning of it all: what does the whole indicate, related to the sum of its parts? Because right now, with both my business and much of the state of digital publishing and technology, I can see the pieces, but not how they fit into the vision.

Content tech links of the week

- What will web experiences look like in the age of LLMs? Designer David Hoang offers some hopeful scenarios.

- My line recently is that internet publishing is currently Deadwood, i.e., a semi-lawless state barely held together by its own powermongers. Case in point: The Robots.txt file is ineffective for controlling web scraping of copyrighted content, on The Verge. If you publish on the internet, it is open season for anyone to crawl and plagiarize your content, and it always has been.

- The New Inquiry tackles the weird TikTok doublespeak its users have created to bystep algorithms perceived to censor sensitive topics. It's a bit academic and theoretical rather than reported and practical, but still a fun piece.

- British GQ stops "feeding the algorithm" for pageviews and instead makes changes to increase time on site and reach new audiences, per the Press Gazette.

The Content Technologist is a newsletter and consultancy based in Minneapolis, working with clients and collaborators around the world. The entire newsletter is written and edited by Deborah Carver, independent content strategy consultant, speaker, and educator.

Advertise with us | Manage your subscription

Affiliate referrals: Ghost publishing system | Bonsai contract/invoicing | The Sample newsletter exchange referral | Writer AI Writing Assistant

Cultural recommendations / personal social: Spotify | Instagram | Letterboxd | PI.FYI

Did you read? is the assorted content at the very bottom of the email. Cultural recommendations, off-kilter thoughts, and quotes from foundational works of media theory we first read in college—all fair game for this section.

Last night I watched Instrument, a 1999 documentary about the legendary Washington, D.C., hardcore band Fugazi. I felt very un-punk by comparison, as I always do when I consider Fugazi and their label Dischord, forever heroes of independent publishing. The film is worth it for the footage of 1990s east coast sensitive hardcore teenagers waiting in line to see a punk show at a church hall, not a cell phone in sight. At least, if you were one of those kids in line, you'll like it.