In this issue:

- A long intro about tech and media

- Upcoming events!

- Wyatt on batch cooking for content

- A Q4 special in the Chum Bucket

- In links: a directory of new social spaces

Apologies to our readers outside the US — this intro is specific to American culture, but I'm assuming it might spill into your country's tech and media industries as well.

Recent internet discourse has been churning out babble on both ends, declaring our current state of platform-driven internet and the rise of artificial intelligence to be either a massive opportunity for growth or irrevocably horrible and beyond repair. I have minimal tolerance for takes on either side, since they tend to be produced by myopic men who spend their days pontificating online instead of conversing, screen-free, with other people.

Andreessen's techno-optimism memo, nigh unreadable and dripping with the folk-economics Babbittry of his Midwestern upbringing, clashes once again with the east coast media industry's tired insistence that they are being robbed of their influence without warning. Some other dude brings up Wired, and no one prominent discusses what properly managing networked communications look like at a practical level, even though there are plenty of examples of what good looks like that have existed for years. (I recommend the excellent Everything in Moderation newsletter if you want to learn how actual people are working hard to keep the internet tolerable with laws, policies, and yes, more software.)

Wired, for its part, retracted an opinion piece earlier this month about Google's "manipulation" of search results that revealed its editors didn't know what "phrase match" keywords are or that paid search algorithms are different from organic search results. As the most prominent legacy publication covering tech, Wired's retraction was extremely embarrassing and indicative of the fact that most reporters and editors covering big tech regularly demonstrate that they have no idea of how the software itself actually works, even when that information is easy to find online, and thousands of developers and marketers would be happy to describe it in detail. It's a problem, and it means we're always keeping the discourse at the level of "will we live in space?" instead of something, anything more useful.

Neither Andreessen and his Silicon ilk nor legacy media's coverage of digital communications looks like a fair or reasonable point of view, and both suggest that humans working in tech industries are powerless to the effects of technology, media, and markets. All look at the sun, but never in the mirror, and it's exhausting.

Neither point of view recognizes the actual state of the American digital knowledge worker, one that's conflicted about their love of the medium and disgusted with the screaming it encourages, and wants to live well and generally be better, if we can. We chose careers in tech for possibility and change, yes, but not blind optimism.

No, I haven't done extensive research on the knowledge worker mindset (other fish to fry), but I also know it's not just me. I mean, look at all the people who genuinely enjoy LinkedIn but also regulate their children's screen time. Listen to the sighs of everyone who is tired of managing logins and interfaces for every aspect of life, from medical care to finance to education to ordering at a restaurant to riding public transportation.

The current discourse about technology looks more like mass media paternalism of the 20th century over the nuances found in quality networked, collaborative communications: men (almost always) screaming past each other, never acknowledging the thoughts or opinions of the people they assume to be listening. Neither side listens to constructive criticism from their audiences, and neither makes concerted efforts to adapt beyond the provincial views of their limited industries. Community, either around technology or media, can't thrive if we don't fucking bother to use our complex human brains to understand others' points of view.

I do not want the digital media business to feel like an ocean of giant sharks or of flippant sunfish either. I wish we didn't keep having this same conversation, and I wish more of those involved would demonstrate that they care about the audiences and lurkers who, en masse, actually make them more money than the sycophant commenters who "generate" opinions daily.

My view has always been: Make the internet you want to see. Big tech can be bad, but there are other ways to navigate the ecosystem. The takes weren't meant for you anyway. Read Babbitt and realize how old tech's ideas of progress are. Read Smashing Magazine and remember that good people are still at it. Check out our list of links this and every week. Stop reading websites that use Outbrain to generate revenue because they're not on the side of quality. Keep reading whatever feed gives you pleasure, or create your own.

Let's evolve the discussion.

And now, our brilliant managing editor Wyatt Coday reflects on the similarities between prep cooking and content creation.

–DC

Sponsors and promotions

Just this once, don't be a lurker.

Help shape our content. Complete the 2023 audience survey and receive a complimentary ticket to our November 3 salon: Practical AI for content professionals.

Take the audience surveyUpcoming events

- November 3 | Practical AI for content professionals: A live salon about how to work with the robots - virtual event

- December 1 | Never go out of style: A live salon about content sophistication - virtual event

Please join me in my media production kitchen

by Wyatt Coday

In this first entry into our new Team of One series, which details the ins and outs of running a solo media business or independent content team at a larger organization, our managing editor Wyatt Coday takes inspiration from the restaurant world and funnels it into content creation.

Months after quitting my job to pursue full-time self-employment, I'm dreaming of working less. I'm a skeptic when it comes to productivity culture, especially when we're talking about meaningless scaling and infinite apps promising to squeeze gold out of immaterial time.

But as a business owner who pays for premium health insurance out of pocket, has a professional practice that requires some powerful but expensive equipment, and desperately needs more vacationing, I'm always toying with efficiency hacks. Recently, I've found that getting things done in a timely manner might be simpler than I thought.

My solopreneur art and media business involves attracting new audiences via my newsletter, but my content production workflow usually bottlenecks whenever I try to add a large, lucrative, and meaningful project to the mix. Since these expansive projects provide a sizable amount of my income, I end up having to balance my regular content production with the demanding research and community-driven programming I'm developing on the fly. My clients are primarily artists who are similarly working alone and trying to stabilize their creative business.

Enter large-batch cooking.

Yes, we love food, cooking, and restaurant metaphors at The Content Technologist. We also know and love many restaurant workers who routinely confront the logistical challenges associated with cooking for hundreds if not thousands of people on a given day. I grew up working in a restaurant with my best friend Ben, who has worked in some of Chicago's most venerated kitchens. When it comes to surviving the dinner rush, Ben's production strategy hasn't changed a wink since he started as a prep cook when we were in high school.

Imagine clocking into your restaurant job around 9am and seeing that the 17-year-old kid — the one you taught to handle a knife just a year ago — had already finished 90 percent of the prep work necessary to keep the kitchen running throughout the day. Ben was something of an anomaly, but the cooks in charge loved him because he cut their workload in half.

But it wasn't just them, everyone at the restaurant loved him. He even made our bosses' jobs easier. With Ben around, they had more time to experiment with specials and optimize how perishables were stored in the deep freeze. His prep strategy — lump similar tasks and get it as much done at the outset — was a real game changer.

From prep cook to executive chef

Ben sometimes calls me after he closes the kitchen. Last year, he left his executive chef job to take on a more managerial role at a new restaurant. When I first heard about this transition, I was excited to hear that he would be spending less time in front of the burners. Then reality set in.

More than work, Ben is addicted to cooking. Specifically, he is addicted to the logistics of cooking. Having immersed himself in restaurants since he was a teenager, he can now rattle off the price of local vegetables and meats, calculating the difference between them in his head down to the cent. As a result, he's saved nearly every restaurant he has worked at thousands — and recently millions — of dollars a year in food costs. And he does this by staying close to the production process, meaning he cooks in his new job even though he doesn't have to.

Busy as he may sound, Ben takes more vacations than I do (none). Gets to see his friends and family more often than I do, and he is especially savvy at building his savings account. Obviously, I look up to him. He is family to me, and much of what I've learned about managing logistics comes from talking to him and watching how he works. We are both type-A, action-oriented people, but he is somehow always faster and more efficient than I am.

But I digress. Let's talk about newsletters.

Newsletter as experimental kitchen

At the beginning of my self-employment journey, my newsletter was the engine of my business. It shaped my plans, helped me establish a small but engaged audience, and helped convince me that my lean solo startup was financially viable.

But a month ago, when I began the first session of the two-week digital strategy course I planned, I realized that I was running on fumes. The course brought in more money, and I knew that it was an opportunity to bring on additional clients, so I put my energy and focus there after letting my subscribers know that I would be on hiatus for a few weeks.

That hiatus lasted a month longer than planned, which isn't the longest stretch of time. But I noticed, and worried about, how difficult it was to resume. In the weeks that followed the course, I made several attempts to sketch out ideas for posts, but ultimately nothing felt like it would resonate or provide useful information. I squirreled that content away in my slush folder and gave up.

Ben called me around this time. We had discussed a podcast project during COVID, and now that the restaurant industry was more stable, his ideas about the podcast were percolating again. I walked him through the process of structuring and scoping intellectual property proposals and outlined how I would navigate selling his idea, something I do regularly with my clients.

Then it dawned on me that I had actually learned my scoping process from Ben. He had already given me a solution to my newsletter production problem.

The trick is to distill before you produce

When you have to feed thousands of people everyday, you quickly learn to distill common ingredients and create a pipeline that helps you track inventory, conduct quality control, and keep an eye on sales figures.

Ben is an inventory master, and I have seen him help make several restaurants considerably more profitable by keeping tabs on what comes in and out of the kitchen. During this process, he not only reduces food waste, but develops a data-backed idea of what most people coming to his kitchens want to order and why.

Any time there are quality ingredients that might go to waste, he offers a special that, once he's done all the prep work, can be made to order by any of the chefs working the line. Investing time and energy at the beginning means that execution usually only takes a few minutes. The extra prep transforms materials that were about to become valueless into enticing dishes.

A masterplan for master-sized problems

I've been conducting a similar experiment with my newsletter. Instead of writing a fresh piece every week, I now make a master document every month, sketch out my ideas in long form, then break them into smaller, denser pieces so that they’re ready on Wednesday morning, when I usually hit the publish button.

To execute on the master plan idea, I had to pick a specific topic that I could use to explicate larger concepts and investigate for at least a few months. I chose a research project that addressed needs my clients had mentioned, who all mentioned growing aspects of their professional practices that they had previously considered secondary.

I mapped out how I could take some of the content that would otherwise go into my newsletter and repurpose it in various ways.

For example, some could be sold to other publications or translated into video content on social, which usually translates to new subscribers as well.

The experiment is still live, meaning that I haven't yet drawn full conclusions, but the most significant improvement I've noticed is that I no longer have weekly writer's block. I'm also considerably more interested in the research I’m conducting because it's feeding back into the content I'll create in the months ahead.

Savor the good ideas

In the restaurant industry, you would never offer a dish without tasting it first. If you're a savvy restaurateur, you may even choose to time your newest offerings to coincide with events, holidays, or consistently busy periods to optimize your sales as well as the data you collect.

In terms of solo newslettering, whether you're a team of one at a brand or going it alone, consider taking your product to a larger pool that gets more attention. Strategically bottling your ideas and placing them with larger, more resourced publications should definitely have its own page in your playbook. I also realized that the social aspect of reporting and interviewing the stakeholders for my research project not only provided an outside perspective, it would also develop a new side of my professional network and cultivate a bit of a fan club.

Conversation is social networking the old way, the type that happens around a table at a meal, with people you know and respect. It's also great fodder for content creation because conversations are stories that tell themselves.

Like food, writing is even more enjoyable when it's a social activity. Treating your writing as an excuse to grow your network is an almost bullet-proof way to better understand your business and the market it serves. When you actually hit the pavement and find other voices to populate your stories, you've also created an inbound audience — who doesn't love to see their work and accomplishments recognized or celebrated?

The world has plenty of bad news, which we can't ignore but also can't do much to change. But, sprinkling some deserved attention on colleagues and collaborators shows that you know how to conduct the conversation and highlight the less visited corners.

And like Ben at the restaurant, going through the process of planning and preparation ensures that our best ideas, the most expensive ingredients, are used efficiently and meaningfully. In that state, we're not racking our brains for content ideas every day. Instead, we're creating a workflow, an order of operations that can be packed with more flavor, more predictability, and an accurate sense of scale.

Wyatt Coday is the managing editor of The Content Technologist, as well as an artist, writer, and researcher who lives in Los Angeles. She directs NOR Research Studio, a research design firm that develops intellectual property for artists, nonprofits, and media companies. She also contributes to DISPASSION, a newsletter about art, media, and detachment.

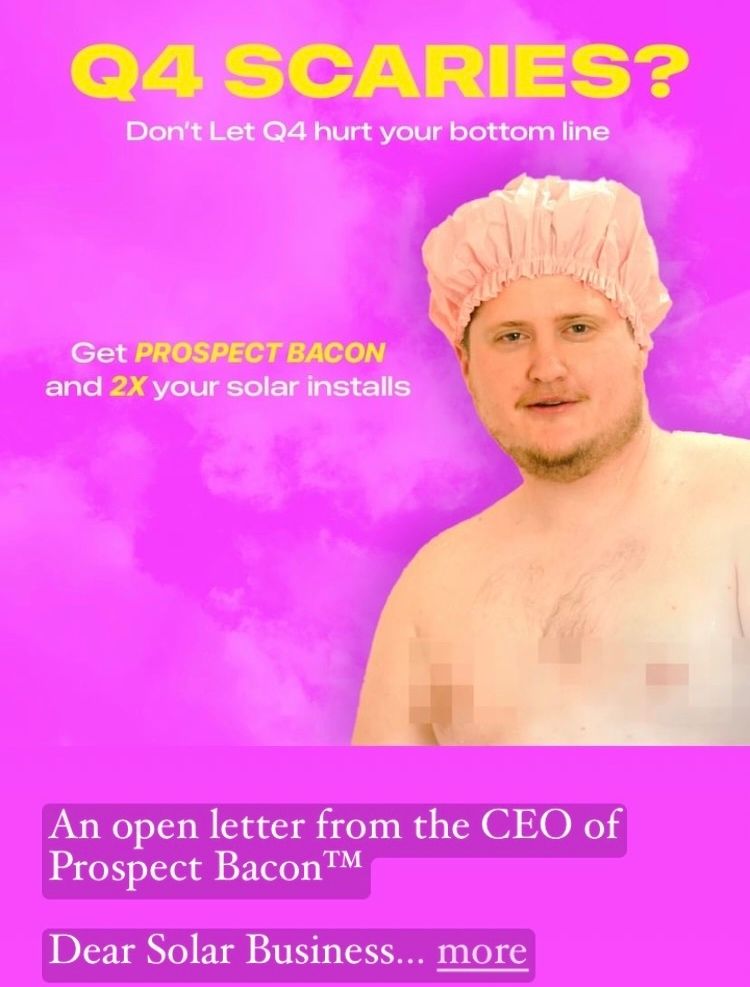

From the bottom of the chum bucket

Our weekly chum bucket explores all the weird programmatic ads we find on social networks. Because "targeted advertising" is a weird, weird thing.

This week's submission once again comes from production assistant M.E. Gray, who does not own a solar paneling business but did receive this ad:

Sponsors and promotions

Did you enjoy this week's newsletter?

Let us know. Take the survey. Get a free pass to an upcoming virtual salon event.

Take the audience surveyContent tech links of the week

- Check out New Public's brand new Digital Spaces Directory to check out how to connect with others on a social internet that has nothing to do with the platforms you already know.

- Yet another very good explainer of large language models (LLMs) from Data Sci 101. It clearly states that LLMs aren't search engines (yay!) and outlines opportunities and pitfalls of tools like ChatGPT in plain language.

- Former Buzzfeed News reporter and internet rockstar Katie Notopolous has some ideas for How to Fix the Internet in the MIT Technology Review. The piece is more than a little reductive about the cycle of business incentives that influence technology growth and political economics — it is MIT, after all — but it's good.

- In Inbox Collective, Claire Zulkey explores the inner workings of newsletter-related communities.

The Content Technologist a company based in Minneapolis, Los Angeles, and around the world. We publish weekly and monthly newsletters.

- Publisher: Deborah Carver

- Managing editor: Wyatt Coday

- Production assistant: M.E. Gray

Collaborate | Manage your subscription

Affiliate referrals: Ghost publishing system | Bonsai contract/invoicing | The Sample newsletter exchange referral | Writer AI Writing Assistant

Did you read? is the assorted content at the very bottom of the email. Cultural recommendations, off-kilter thoughts, and quotes from foundational works of media theory we first read in college — all fair game for this section.

It has been a rough year, but I'm in a better place than usual, and certainly a healthier mental place than I was 2 or 20 years ago.

I've been thinking a lot about Elliott Smith, who passed away 20 years ago on October 21, and whose death hit hard at the time. For a number of personal reasons, I don't need to explain. His songs remain among my all-time favorites.

All this is to say: take care of your people, especially your artist friends who don't think they belong in this world. Let them know you're in their corner, especially when it's rough.