This is the fourth essay in an ongoing series about the technologies that underpin natural language understanding (NLU). I recommend reading this week's essay, about the cultural impact of transformers, as a companion the previous piece, about how transformers function:

Transformers are the central structural innovation in the recent success of large language models, whose primary purpose is to understand and generate language. Markets are rising and falling on the promise of these language models: will they replace human knowledge workers with PhDs and institutional authority? Will they replace writers, designers, journalists, editors, and creative workers? Will they devalue the contributions of scientists, doctors, and researchers? Will they enable businesses to do all of the above to ultimately reduce the cost of human knowledge while solving for errors in human judgment?

The answer isn't in the endless model releases or testing benchmarks—none of which seem to hold much weight when the engineering degrades after rapidly scaled use. For me, the secret to the architecture's potential—and potential failings—is clearly articulated in the primary text: "Attention Is All You Need," academic-style research funded by a global corporation, commonly known as the Transformer paper. As the most widely cited and influential source in current AI architecture, the language and assumptions in the Transformer paper reveal perspectives and ideology baked into the production of language generators.

To put it less academically: Let's close-read the Transformer paper. It presumably changed the world. Its authors made their careers from the manufacture of language, and their employer is poised to profit immensely. Many of us, with our less productive humanities degrees, are overeducated in the interpretation of language. Let's put those advanced degrees to use!

Our primary texts:

The 2014 paper that defined Attention in machine learning

Corporate machine learning research is a primary source text

As content professionals, researchers, and information architects it behooves us to pay closer attention to original research papers than to third-party discourse. Machine learning engineers publish their ideas for public discussion. They present the math, accompanied by their description and interpretation of the math's function. The Transformer paper is a primary text in shaping the assumptions behind the engineering, function, and eventual regulation of LLMs, like the Geneva Conventions or the Declaration of Independence. We do not have to understand the math itself to understand the meaning of the words on the page.

We can't expect artificial intelligence researchers to understand all aspects of human communication and media theory beyond computational linguistics. But it's fair to scrutinize their words and methodology. Language retains meaning, regardless of whether math is involved in its production. The words we publish and hold up for peer review remain the best representation of our brains at work in the digital world. A published paper is the best way to look closely at the foundational assumptions of LLMs. And those begin with pop culture.

I don't believe in Beatles; I just believe in how their work is publicly misinterpreted

As noted in our last issue and first described as fodder for a hero narrative in a 2024 Wired article, the name "transformers" derives from the children's toy. It's easy to mock: a recent complaint among my friends concerns our 40-ish spouses' retention of and reverence for their childhood action figures and vintage electronics. But I have empathy. Consumer culture's embrace of nostalgia turns us all into Disney adults for one franchise or another.

I'm far more in awe of the other pop anecdata reported in Steven Levy's Wired feature on the Transformer paper's creation:

A couple of nights before the deadline, Uszkoreit realized they needed a title. Jones noted that the team had landed on a radical rejection of the accepted best practices, most notably LSTMs, for one technique: attention. The Beatles, Jones recalled, had named a song “All You Need Is Love.” Why not call the paper “Attention Is All You Need”?

The Beatles?

“I’m British,” says Jones. “It literally took five seconds of thought. I didn’t think they would use it.”

For years, I did not see The Beatles reference in the title of the Transformer paper, not because I am unaware of The Beatles. Come on. "All You Need Is Love" is ubiquitous in mainstream Anglo-American culture, and I like The Beatles as much as the next rock fan.

I missed the reference because it's poorly executed. In the parlance of parody writers, the replacement does not scan, and the callback is clumsy. "Attention" is three syllables. "Love" is one. We can't easily swap in "Attention" if we want to maintain the cadence—and the meaning—of the song. The authors admitted that they didn't pay much attention to the words they chose, and just because one is British does not mean one has the chops to riff on the first Lennon/McCartney earworm that crawls in. Skilled communicators understand that poetic license is a privilege.

Even without the Beatles callback, "Attention Is All You Need" reads like a Lana del Rey variation on The Life of a Showgirl. It's oddly specific and somehow blind to the established cultural entity of the word "attention," which since the early 2000s aligned with both the "attention economy" and "I can't believe you think I like attention."

It's a word that's easily disambiguated, and it's a curious choice considering its function.

The origins of the "attention mechanism" metaphor

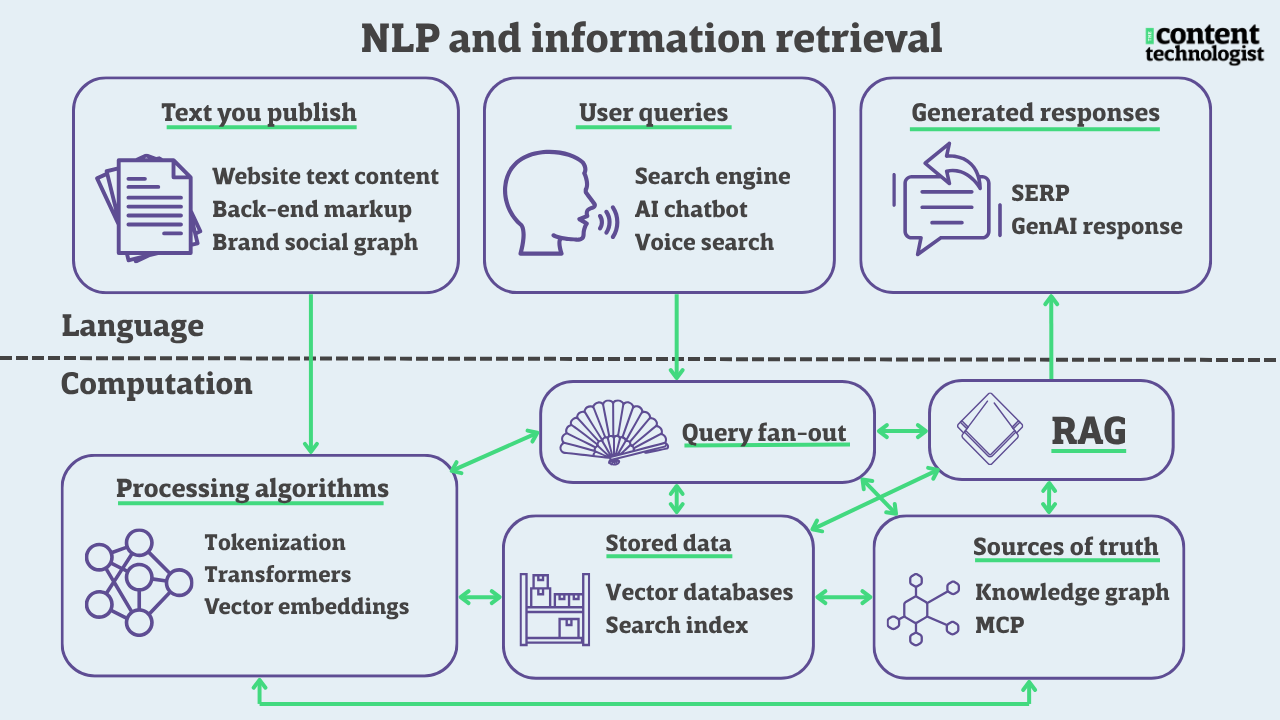

Google's researchers didn't coin the term "attention mechanism"; that architecture was named by academics in 2014. In that research, "attention" represents a calculation of the probability of "annotations"—or mathematically represented relationships between embedded vectors in a query. Machine learning assigns weights to annotations, and the "weighted sum" of those annotations form a "context vector"—the probability that the query lives in a specific semantic context.

"Attention mechanisms" encode the relationships among words in training data to predict the context of a query. They call upon previously learned textual data, and their function does not correlate with "attention" functions in the human brain. If we were drawing precise connections with neuroscience, "attention mechanisms" are more accurately "perception mechanisms." They calculate a semantic environment based on previously learned context, not a learned focus on the essential meaning of the query.

But there is no "perception economy." While the age of identity politics and representation valued being seen and heard, we never called it "perception-seeking behavior." Attention is a word that likes attention, especially in mass media discourse. It's sharper and punchier, especially when you combine it with a Beatles lyric. Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da, it's attenTION!*

It's such a valuable metaphor that the writers of the transformer paper chose to modify "attention" instead of coining a new term for their architectures: "multi-head attention" and "self-attention" somehow transcend sophomoric snickers to become the central innovations in a world-destabilizing technology. Whether intentional or not, preserving "attention" as a function of "transformers" was critical in its widespread adoption.

*I'm sorry. Thinking it felt terrible, and writing it felt worse.

Reconciling ML tunnel vision with multidisciplinary awareness

Words themselves carry their own embedded context vector, often subtextual (per Raymond Williams). That context vector is determined and mitigated through the intentional manufacture of political and sociological consent (per Walter Lippmann, Noam Chomsky, and Edward S. Herman). And with the amount of capital, energy, and anxiety sunk into technology that advertises itself as "attention," it's fair for wordsmiths to pay our own.

Machine learning scientists may argue that their discipline's specialized vocabulary was never intended to be analogous to other fields, but the widespread portrayal of machine learning as a destructor of professions in every other field renders that point moot.

An over-reverence for STEM at the expense of any other discipline leads many to believe machine learning research is on its own plane, above all other academic and corporate interests. That assumption is wildly irresponsible at the scale of the AI hype, particularly in this political moment. The Transformer paper, or any of the papers that underpin the core technology, are not above examination. They contain no signs of divine intervention and are fallible human ideas.

Data-driven ML engineers appropriate pop culture in their work at the same rate as 20-something Substackers. A transcript of Casey Newton and Kevin Roose's Hard Fork podcast mentions that the authors of the Transformer paper were inspired not by neuroscience or human behavior, but by the film adaptation of Arrival, another speculative future forged through the cultural production machines of book publishing, then Hollywood, and finally the "attention economy" arm of the New York Times. The celebration of the transformer's importance rests on an exceptionally obtuse basement guy reading of anecdata, not the facts of the primary documentation.

Ted Chiang, author of the short story that inspired Arrival, famously critiqued ChatGPT as "a blurry jpeg of the web." If it's true that his intellectual property was co-opted to "inspire" the central architecture that powers LLMs, then the machines themselves are a blurry compression of his original plot device. For all his brilliance and prescience, I doubt the ouroboros—or, in ML terms, the multi-head attention mechanism that reads context forward and back—was Chiang's intention.

Laze is all you need

Lazy pop interpretation is a hallmark of AI-related communications. It's in the Ghibli memes, Heinlein references, and Star Wars allusions. It is easy to be sloppy with language and make gobs of money, as long as you are male, you have rich friends, and you spend a lot of time tapping the glass instead of engaging with normal people. If there is magic in machine learning, it's in the formula of Founder Mode behavior, in the magical thinking of nights out at Davos, and not in the LLM itself.

People who care about words, about their origin, about their effect on human communication, pay attention to language and cultural significance in a way that the Transformer paper's writers did not. That continued lack of precision from executives; the repeated insistence that AI will "democratize" creative labor and knowledge work; the validation from the gullible tech press, who are supposed to be looking out for words and annotations and context (no vectors needed)—we're living in a perfect storm of semantic dehumanization.

Natural language understanding and LLMs remain an incredible innovation. The fact that humans have created language generation machines from mathematics is mindblowing. It's the lack of intention in generative AI's attendant communications strategy that annoys and frightens me. When considering the long-established history of language and the publishing industry, it doesn't feel like a stretch to ask those intending to replace me to be more considerate with their words.

"Attention is all you need" would never pass the red pen of a fastidious editor or a brand director, but for all reasons listed above, the disambiguation is a master class in tech industry marketing. "Attention" is an embedded ideology to distract from the practical function of technology, right up there with "hello, world," an anthropomorphism conceived in the R&D arm of last century's great monopoly, AT&T.

As far as both tech and media narratives are concerned, the computers will become human, regardless of the better judgment, intellectual tradition, and carefully honed skills of the knowledge workers lending corporations our brains. Writers and other comms professionals learned to value intention... when in hindsight, it's looks increasingly like the better parts of our education in language and communication were a bad investment. Turns out all we needed was a flaccid familiarity with Boomer pop, a fondness for action figures, and a ticket to the movies.

Read earlier essays in this series